Menu

Champlain through the eyes of North Americans

Samuel de Champlain has come to mean many things to many people. His varied identities and activities have inspired various kinds of thinking and writing about his life and accomplishments. These different approaches contribute to our understanding of Champlain and his role in the history of Ontario and North America more broadly. They also contribute to our understanding of what it means to be Canadian and how this identity is formed and considered over time.

Many people with different perspectives have celebrated the life of Samuel de Champlain.

Champlain the explorer

Historian Samuel Eliot Morison described Champlain as “… one of the greatest pioneers, explorers and colonists of all time.” – Samuel de Champlain: Father of New France, 1972

“After spending that winter in Huronia, Champlain was able to make the most important contribution since Cartier to what was known of the interior of the continent.” – Marcel Trudel, The Beginnings of New France, 1524-1663, 1973

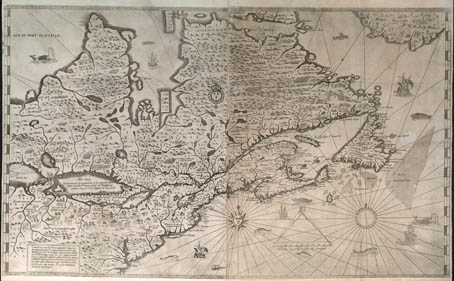

Champlain the map maker

“The cartography of Samuel de Champlain marks the beginning of the detailed mapping of the Atlantic coast of North America north of Nantucket Sound, into the St. Lawrence River Valley, and, in less detail, the region up to and including the eastern Great Lakes.” – Conrad E. Heidenreich and Edward H. Dahl, “Samuel de Champlain’s Cartography, 1603-32,” 2004

“Although today Champlain is best known to the general public for having placed on a permanent footing the French presence in North America, individuals interested in the history of cartography and of exploration hold him in high regard for the exceptional quality of his maps and plans.” – Conrad E. Heidenreich and Edward H. Dahl, “Samuel de Champlain’s Cartography, 1603-32,” 2004

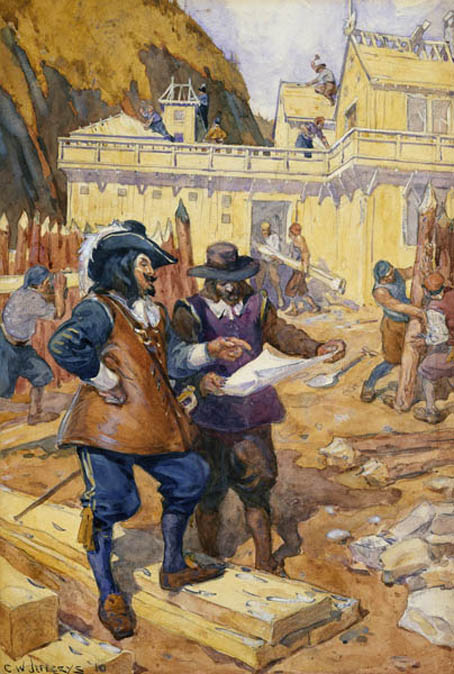

Champlain the founder of Quebec and father of New France

“The French, in the early years of the seventeenth century, had returned to the St. Lawrence Valley in a fresh attempt to establish a commercial colony. What success they enjoyed they owed largely to the persistence and enterprise of one man, Samuel de Champlain.” – W.J. Eccles, The Canadian Frontier, 1534-1760, 1969

Champlain the sailor and soldier

“Samuel de Champlain was the most versatile of colonial founders in North America; at once sailor and soldier, writer and man of action, artist and explorer, ruler and administrator.” – Samuel Eliot Morison, Samuel de Champlain: Father of New France, 1972

Champlain the builder of relationships with other nations

“Champlain learned that in order to be accepted and taken on exploring trips, close personal relations and trust had to be built with Native leaders.” – Conrad Heidenreich, “The Beginnings of French Exploration out of the St. Lawrence Valley: Motives, Methods, and Changing Attitudes towards Native People,” 2001

“He was the first European to clearly see and recommend that, in order to explore and live in Canada, certain adaptations had to take place to the Native presence and the physical environment. The way to overcome physical obstacles to exploration was to become accepted by the Native people and learn to proceed with their help.” – Conrad Heidenreich, “The Beginnings of French Exploration out of the St. Lawrence Valley: Motives, Methods, and Changing Attitudes towards Native People,” 2001

Champlain the leader

“Champlain’s greatest achievement was not his career as an explorer, or his success as a founder of colonies. His largest contribution was the success of his principled leadership in the cause of humanity. This is what made him a world figure in modern history. It is his legacy to us all.” – David Hackett Fischer, Champlain’s Dream, 2008

Different perspectives: Questioning Samuel de Champlain

As a historical figure, Samuel de Champlain has provoked much

discussion. While his many identities and accomplishments have been

celebrated, a number of people with different perspectives have

questioned his motives and actions.

Questioning Champlain’s exploration and colonization of New France

Although Champlain explored much of what is now Quebec and Ontario, it is important to remember that the land he encountered was not empty and available for the taking, but instead was inhabited by numerous Aboriginal nations that hunted, harvested and fought over territory in their own right long before Champlain or any other European explorers visited what is now North America.

“Facing up to the past means owning all of our history, rather than perpetuating the myth of white settlers creating civilization in uncharted wilderness.” – Joyce A. Green, “Towards a Détente with History: Confronting Canada’s Colonial Legacy,” 1995

“They are the First Nations, the founding people, because their ancestors were living here on Turtle Island, with their own laws and institutions, before the Celts swarmed over Britain and the Gauls invaded what is now France. They had municipal government, international agreements, sophisticated community structures, and an established justice system when Champlain’s men were toughing it out [on] the St. Croix River.” –Assembly of First Nations, To the Source: The First Nations Circle on the Constitution, 1992

Quick fact: The First Nations Circle on the Constitution made an important contribution to the significant discussion and negotiations concerning constitutional reform taking place in Canada at the time. This debate resulted in a package of proposed amendments to the Canadian Constitution called the Charlottetown Accord, which was ultimately defeated by public referendum in 1992.

Questioning Champlain’s relationship with Canada’s Aboriginal people

While certain images and writings reflect the perspective that Champlain’s relationships with his Aboriginal allies were both positive and reciprocal, other perspectives suggest that he did not attempt to fully understand the Aboriginal people he met, and that his actions were not motivated by good will, but rather by a desire on the part of his own nation to acquire land and monopolize land and resources and to convert Aboriginal people to Christianity.

“There is considerable evidence that, even in these early days, Champlain was temperamentally incapable of understanding the Indians on their own terms. A relatively unreflective and self-centred man, he automatically used the prejudices he derived from his own culture as a yardstick for measuring other people.” – Bruce Trigger, “Champlain Judged by His Indian Policy: A Different View of Early Canadian History,” 1971

“The French believed the natives would eventually become the subjects of their king and worshippers of Christ. Thus, the very foundation of the relationship between the French and the natives was based on a serious misunderstanding.” – Denys Delâge, “Uneasy Allies,” 2008

Questioning Champlain’s status as a celebrated historical figure

The life and deeds of Samuel de Champlain, like those of any prominent historical figure, have been both commemorated and criticized. While certain perspectives elevate Champlain to the status of hero, others question his motives, while still others make the point that his accomplishments have been exaggerated to serve the larger purpose of creating a national identity for Canada.

“In the crowded pantheon of early explorers there are only a few whom I would care to invite to dinner. Cartier and Champlain are admirable historical figures, no doubt, but both were hard cases: the former was a kidnapper, the latter an assassin, in each instance their victims were unsuspecting Indians.” – Pierre Berton, My Country: The Remarkable Past, 1976.

“Champlain? Not very stimulating, the old founding father. His wife seems to have been a lot more fun. Poor guy, always stuck with the building of his habitation at Quebec with the English overrunning it time and again … O History! That inexhaustible storehouse of stories to be embellished indefinitely.” – René Lévesque (former Québec premier), Memoirs, 1986

Such differing perspectives contribute to and broaden our understanding of Samuel de Champlain as a historical figure in the stories of Ontario, Quebec and Canada. While they do not lead to a consensus about his life and accomplishments, they do stimulate thought and discussion, and further reading, research and writing, and so keep Champlain’s legacy alive in the 21st century.

Educators: Things to think about …