Menu

Cold War air defence

Introduction

On July 27, 1953, an armistice brought an uneasy end to three years of fighting on the Korean peninsula. Among the 26,000 Canadians who served, 312 were killed in combat. The end of the Korean War was an important turning point in Canadian military history because it was followed by a shift away from conventional warfare. Instead, Canadian military strategy focused on addressing the threat of nuclear war with the Soviet Union.

As Canadian and United States intelligence calculated, Soviet bombers would approach from the Arctic Circle, thereby transforming the Canadian North into the frontline of continental defence. To counter this threat, Canada and the United States organized a multifaceted defence network to detect and neutralize Soviet bombers. This defence network was consolidated under what would become, in 1957, the North American Aerospace Defence Command (NORAD). As this section explores, the defence of North America against a Soviet nuclear threat significantly impacted Ontario through the development of its aviation industry and military bases.

Ontario aviation

After the Second World War, the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) needed a state-of-the-art interceptor to deter Soviet aggression. The RCAF turned to A.V. Roe Canada Ltd., also known as Avro Canada. The company was based on the former Victory Aircraft Limited facilities in Malton, which the Canadian government sold to the Hawker Siddeley Group Ltd., who established the facilities as a subsidiary company. Avro Canada also purchased Turbo Research Inc., which was a government-funded organization that developed jet engine technology during the Second World War. After acquiring Canada’s leading facilities and designs, Avro Canada quickly established itself as a leader in the aviation industry.

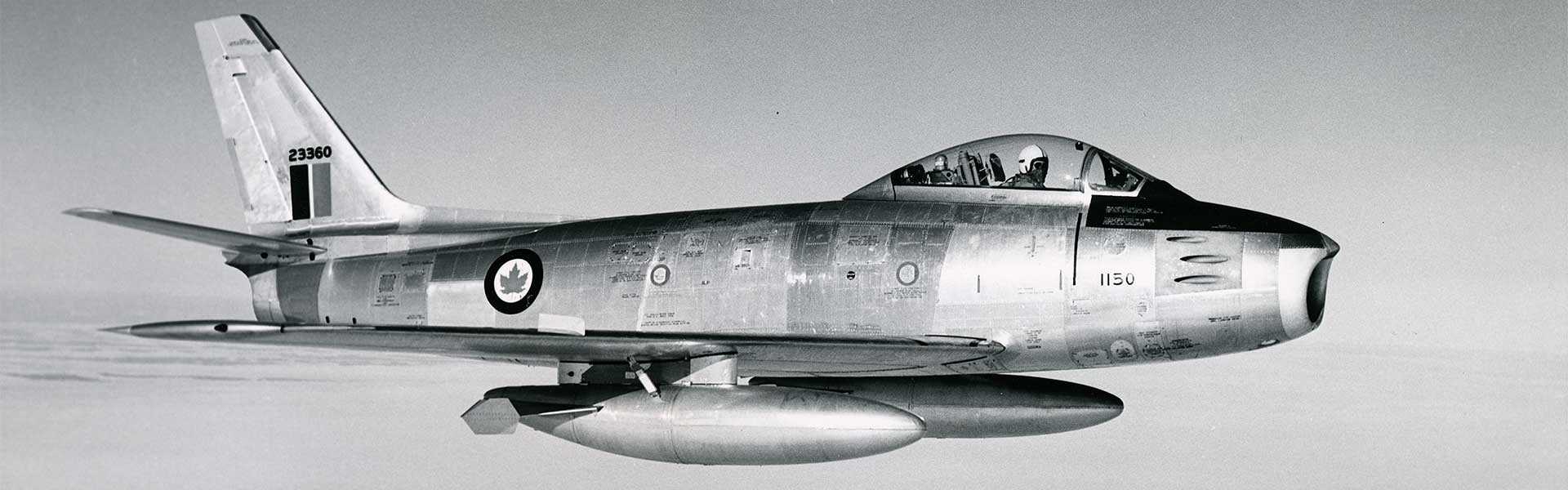

In November 1945, the RCAF and Avro closed a deal to design a new fighter/interceptor prototype. Nearly a year later, another contract was signed to produce the Avro CF-100 Canuck. The CF-100’s initial flight, in January 1950, was a monumental step in Canadian aviation history because it would be the only jet fighter designed and mass produced in Canada. It boasted advanced fire control systems, cutting-edge radar navigation, two seats and an all-weather design. The CF-100 also stood out because it was equipped with two Canadian-manufactured engines that Avro called the Orenda. Based on these features, the CF-100 stood out for its design, performance and versatile capabilities.

As the Korean War began on June 25, 1950, the demand for jet fighters among North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) members increased, especially as the Soviet Union deployed its MiG-15s. The United States Air Force considered acquiring CF-100s, but they came in at twice the cost of the North American F-86 Sabre.

They were further deterred by Avro Canada’s ongoing setbacks. Avro engineers were still addressing design issues and had to implement numerous modifications, as requested by the RCAF. In addition to design adjustments, Avro’s resources were spread thin. Avro was not only developing the CF-100 but it was also delivering Orenda engines to Montreal-based Canadair to upgrade their production of F-86s. Simultaneously, Avro Canada was developing a passenger jetliner, which missed becoming the first passenger jet to take flight by only a few weeks. The Avro Canada Jetliner held great promise, but it was ultimately cancelled to prioritize military contracts. Despite this sacrifice, CF-100 production still fell behind schedule. By the time Canadair manufactured a thousand F-86s, Avro produced only 90 CF-100s. By 1954, production of the CF-100 steadily climbed to a total of nearly 700 planes.

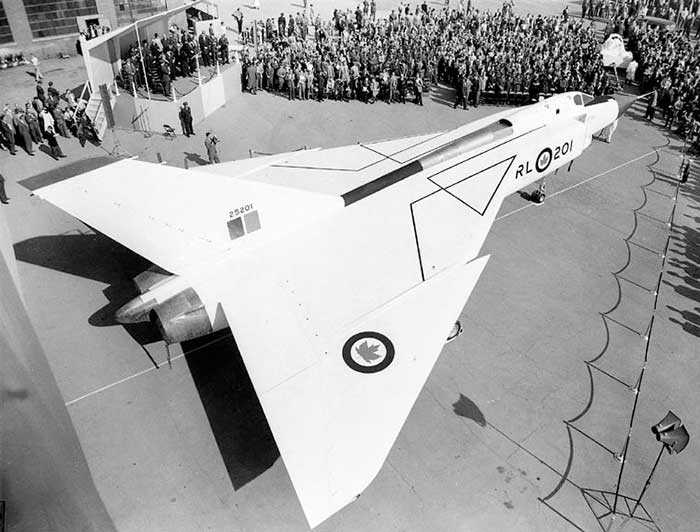

The Canuck was a cutting-edge aircraft, but Soviet aviation rapidly advanced during the mid- to late 1950s and made the Canuck obsolete as a countermeasure to a Soviet nuclear attack. To address this shortcoming, Avro received a contract in January 1954 to design a next-generation supersonic interceptor. The new prototype was called the Avro Canada CF-105 Arrow, more commonly known as the Avro Arrow.

The Avro Arrow shared similar features as its predecessor, including all-weather capabilities, but it offered higher performance. Most notably, the Canuck’s maximum speed of 0.85 Mach was completely outmatched by the Arrow’s record-breaking speed of 2,104 km/hour, which is slightly below Mach 2. The RCAF was enthralled by the design and expressed their intention to purchase between 500 and 600 Arrows with expected deliveries commencing in 1958.

The development of the Arrow was undoubtedly an exciting time in Ontario’s aviation industry. But as fast as the Arrow captivated the people of Ontario and beyond, its source of national pride shifted into that of disappointment.

On February 20, 1959, Prime Minister John Diefenbaker announced that the federal government would no longer purchase the Avro Arrow. Among the primary reasons was that the end of the Korean War and the decreasing likelihood of a Soviet invasion into Western Europe lessened NATO’s sense of urgency. Another important consideration was the Avro Arrow’s price tag. Diefenbaker’s government was committed to fiscal restraint and the projections of the Arrow’s cost per plane ballooned to anywhere between $8 and $12.5 million. Adding to the government’s concerns was the Arrow’s limited utility. On October 4, 1957, the Soviets launched the first satellite into orbit — the Sputnik I. Its launch ushered in the Space Age and opened the acceleration of deploying nuclear weapons through intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). The preferred countermeasure to ICBMs were anti-ballistic missiles rather than interceptors.

In the end, the Avro Arrow was abandoned; the Avro Canucks remained in service until 1981. Nevertheless, Avro Canada — along with the tens of thousands of workers directly and indirectly employed by Avro projects — achieved major feats in aerospace and aviation engineering. Their efforts provided substantial contributions to NATO’s defence and also laid the foundation of space research and operations.

NORAD and RCAF Station North Bay

The philosophy underpinning North America’s defensive strategy was to deter a Soviet attack through offensive and defensive power. Offensive deterrence was premised on the extension of the United States’ “Instant Retaliation” strategy. Similar to the American response to a Soviet invasion of Western Europe, a Soviet attack would authorize a large-scale retaliatory nuclear strike on the Soviet Union, thereby skewing Soviet military calculations against offensive action.

Until the 1960s, Canada did not possess any nuclear weapons, but they were implicated in American nuclear armament. During the Second World War, Canada provided refined uranium from a facility in Port Hope, nuclear research associated with the National Research Council, and participation in the Manhattan Project. After the war, Canada continued to support nuclear armament through the provision of plutonium from Ontario-based Chalk River Laboratories.

In terms of defensive deterrence, Canada and the United States began coordinating continental defence as early as 1940 through the establishment of the Permanent Joint Board on Defence. The emergence of the Soviet threat after 1945, and the Soviet’s development of nuclear weapons in 1949, added a sense of urgency to air defence. As discussed above, defence deterrence involved the rapid deployment of interceptors to eliminate Soviet bombers. To identify an incoming attack, a bilateral agreement was formed to create chains of radar stations in Canada between 1951 and 1957: the Pinetree Line (which accepted servicewomen from the RCAF’s Women’s Division), the Mid-Canada Line and the Distant Early Warning Line. Canada and the United States also centralized operational air force command through the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), which was established in 1957.

By the late 1950s, North American air defence shifted as the Soviet Union made advancements in ICBM technology. The Defence Research Board of Canada concluded that it was no longer a matter of who attacked first but rather how much retaliatory strength remained afterwards to strike back. Hence, through mutually assured destruction (also known as MAD), the Soviets would be deterred to attack with nuclear weapons. As the Soviet Union built up its nuclear arsenal, the RCAF remained committed to intercepting Soviet bombers in the interim, but without the expensive Avro Arrow. Instead, Diefenbaker’s government acquired 66 McDonnell CF-101 Voodoo interceptors from the United States. If the Voodoos were to be effective at neutralizing Soviet jet bombers armed with nuclear weapons, they would require their own nuclear-tipped missiles.

Watch this video of the underground complex at 22 Wing/Canadian Forces Base North Bay, the former home of the 22nd NORAD Region and Canadian NORAD Region. (Photo: Canadian Forces Museum of Aerospace Defence)

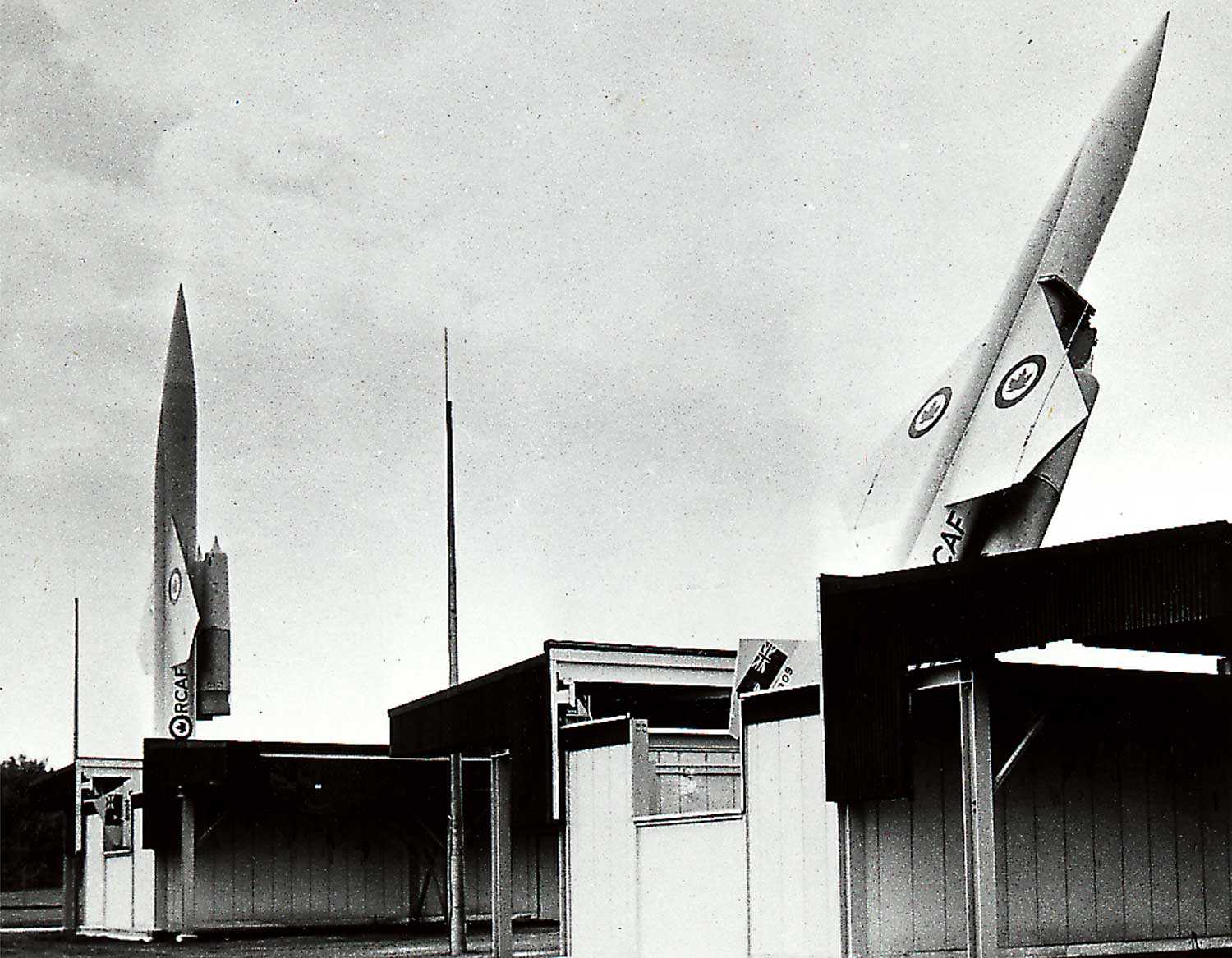

The issue caused a rift in Diefenbaker’s government, however, prompting the 1963 election. Diefenbaker and the Conservative party were defeated by Lester Bowles Pearson and the Liberal party. Under Pearson, the nuclear missiles were acquired in support of NORAD. Financial considerations were not a major factor in the decision since most of the cost was covered by the United States Air Force. In addition, Pearson’s government purchased 56 Boeing CIM-10B Bomarc long-range surface-to-air missiles armed with nuclear warheads.

The RCAF had numerous air bases in Ontario, including bases in Petawawa, Camp Borden, Kingston, Trenton, Centralia, Rockcliffe, Clinton and Downsview, among many others. Perhaps the most significant air base for defence against the Soviet nuclear threat was RCAF Station North Bay.

Beginning in December 1963, RCAF Station North Bay housed most of Canada’s nuclear arsenal (the remainder were stationed at La Macaza, Quebec). Between the late 1950s and early 1960s, RCAF Station North Bay was transformed into a highly defensible base that operated as the command centre for the Northern NORAD Region. Similar to NORAD Headquarters in Colorado Springs, or the Diefenbunker near Ottawa, the North Bay military base had an underground complex. Located 183 metres (600 feet) below ground (equivalent to approximately one-third of the height of the CN Tower), the complex had life-support systems and was designed to withstand a four-megaton nuclear blast. It was also equipped with the only Semi-Automatic Ground Environment (SAGE) system outside the United States. This system required enormous computers, which were used for aerospace detection and computing interception courses. By 1964, North Bay’s interceptor squadrons and Bomarc missiles became operational.

By the late 1960s, the Soviet nuclear arsenal shifted into ICBMs. Since Bomarc missiles were not effective against ICBMs, they were removed from North Bay in 1972 by a special United States Air Force division. North Bay has remained an important NORAD base that continues to receive major infrastructure and technological overhauls to continue its vigilant surveillance of North American aerospace.