Menu

Modernizing the Canadian Forces

Introduction

Since the end of the Second World War, the Canadian military has developed new capabilities, structures and roles for its domestic and international operations. Some of these dynamics have been discussed in the section on Cold War air defence, which examines the development of Ontario’s aviation industry and Ontario’s integration into NORAD. This section offers a more generalized chronological overview of military modernization in the Canadian Forces. It aims to provide a sense of historical continuity between Ontario’s military history and the present.

1946 to 1968

After the Second World War, the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China emerged with massive armies and an antagonistic disposition toward democracy and capitalism. Western democratic leaders, who learned the consequences of isolation and appeasement from the origins of the Second World War, committed themselves to being more proactive toward their own collective security as well as the international security of democracy.

Among the post-1945 changes was Canada’s agreement for closer integration with the American military. As early as 1947, Canada established bilateral security agreements pledging to purchase American equipment, adopt American training and further integrate military communications. This was a significant shift because it represented an acceleration of Canada’s alignment towards the United States and departure from the United Kingdom. But Canada was not wholly unique in this regard. In accordance with the Truman Doctrine, the American government declared its commitment to contain Soviet influence and, as a result, the United States heavily invested in reconstructing Western Europe through the Marshall Plan. Building on this pledge and financial support, Western democracies rallied behind American leadership to form the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in 1949. Initially signed by Canada, the United States and 10 European countries, the new organization was a formal military alliance that bound members through their commitment to democratic values, human rights and the then-newly established United Nations.

In 1951, Canada demonstrated its commitment to NATO by deploying an infantry brigade and air division to Germany and France. Canada also deployed military forces to Korea as part of the United Nations Command to defend the democratic South Korean government. As Canada’s contribution to the 1st Commonwealth Division in Korea, a special volunteer-based contingent was organized and called the Canadian Army Special Force. By mid-1951, 8,500 soldiers had been deployed, and by the war’s end in 1953, roughly 20,000 Canadians served. As the Korean War validated Cold War fears of communist aggression, Canada embraced new initiatives for military modernization and expansion. Between 1949 and 1951, Canadian military personnel expanded by 70 per cent. The Liberal Louis St. Laurent government also committed $5 billion to military rearmament. But it was not the expansion of military ranks and military budgets that made this period unique as much as how the military was transforming internally.

Among the most significant changes during this period was the permanent integration of women. By 1947, women in the Canadian Women’s Army Corps, the RCAF Women’s Division and the Women’s Royal Naval Service (WRCNS) were demobilized except for a select group of nurses. Four years later, during the Korean War, military enlistment was falling short of recruitment targets, leading the federal cabinet to re-authorize the enlistment of women. Some gender inequalities were removed, such as unequal pay for single male and female personnel, but many inequalities remained. For instance, married women could not enlist, armed services set female enlistment ceilings, women served in distinct women’s divisions, positions were restricted to non-combat roles, and only nurses were sent to Asia and Europe. Despite these limitations, female enlistment surged in the first year: almost 2,600 women enlisted in the RCAF, 1,000 women in the Army Reserve and 369 in the WRCNS. By the mid-1960s, the number of servicewomen dropped drastically and the armed services contemplated dissolving the women’s divisions yet again. This led the Minister of National Defence to conduct a study on women in the armed forces. The conclusions strongly supported the continuing employment of women as a means of releasing men for more complex tasks. Hence, the study helped secure the permanency of servicewomen, but it did not significantly challenge prevailing gender norms.

Another change in the military was the reorganization and subsequent unification of the three military services. In 1964, the Minister of National Defence, Paul Hellyer, published the White Paper on Defence. It argued that the military required a new structure to fulfill its roles regarding collective defence and international stability, particularly to adjust to the demands of peacekeeping missions. By restructuring the army, the RCAF and the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) into functional commands that combined services, there could be one point of authority to oversee integrated operations. After adjustments to Hellyer’s proposed structures, six commands would be created: Force Mobile Command combined army and tactical air support, Maritime Command combined naval and naval air support, Air Defence Command, Training Command, Material Command, Air Transport Command and, later, Communications Command. On February 1, 1968, the Canadian Forces Reorganization Act took effect and six functional commands were formally merged into the Canadian Armed Forces. Accompanying this unification was the dissolution of the separate organizational structures for women. In addition, Canadian military camps, stations and land-based ships became Canadian Forces bases, green uniforms were issued for all services (notably a shift away from British attire), and rank structure was changed alongside service badges.

In 1968, another significant change to the military would take effect — the creation of new French-language units. Historically, the English language was predominant in the Canadian military. Following the election of Pierre Trudeau in 1968, this new Liberal government pledged its support for the Official Languages Act, which made French an official language of Canada. The military provided an ideal institution to implement this reform. In addition to new French language units, French-language military schools were created, bilingualism became a requirement for high command and French-Canadian representation was prioritized in recruitment and promotion. The implementation of bilingual reforms was not without its pushback but, over the decades, it has achieved remarkable success.

1968 to the end of the Cold War in 1991

As Cold War tensions eased during the mid-1960s and the 1970s, the federal government embraced financial cutbacks and military strength reductions. The Reserves, which had been reoriented toward civil defence during the 1950s, was reduced from 23,000 to 19,000. Canada’s NATO contingent was reduced by half in 1969. And the Regular Force numbered less than 80,000 men and women. Regarding acquisitions of new military equipment, the federal government preferred to purchase outdated equipment from NATO allies for cost-savings and political leverage. The navy became the greatest casualty of fiscal austerity during this period. After 1972, the Canadian Forces would not receive a new warship for 15 years.

In addition to strength reductions, there was also the rising trend of “civilianizing” military responsibilities. At the National Defence Headquarters, political appointees gained more autonomy and there was an increasing number of civilian managers and analysts. As the Headquarters became more bureaucratized, those who preferred traditional structures harboured resentment and resigned, but federal policymakers continued the civilianization effort unperturbed. One area where traditionalists found some success was the restructuring of the commands in 1975. Most air force assets were consolidated under Air Command, thereby allowing a familiar division to re-emerge dividing the army, navy and air forces.

Following the reunification process in the late 1970s, the “Total Force” concept gained traction in the Canadian Forces. The idea was to maximize operational effectiveness through the close integration of Regular and Reserve forces. Such an integration meant that Reservists would train under the standards of Regular Force personnel and require updated equipment. It also meant that both Forces would share an increasingly centralized administration. Support for Total Force restructuring continued throughout the 1980s and was advocated by the 1987 White Paper on defence policy. By the end of the Cold War in 1991, the shift to Total Force had been only partially achieved.

Shifting defence policies, budget priorities and national mobilization strategies, combined with administrative difficulties, obstructed efforts for a more far-reaching overhaul. Nevertheless, the Reserve Force responsibilities in the day-to-day operations of the Canadian Forces was enhanced and its participation in overseas operations increased. Among the important administrative changes was that responsibility for administering recruitment shifted from Reserve units to Canadian Forces Recruiting Centres in the late 1980s. Such a change should not obscure the continued importance of Reserve units because, as in the case of recruitment, Reserve units remained important for attracting recruits and fostering support for the military in their local communities.

In 1971, a Royal Commission on the Status of Women made numerous recommendations to improve gender equality in the Canadian Forces. Nearly all of the Commission’s suggestions were adopted, including the permission of married women to enlist, the standardization of enlistment qualifications and pension benefits, and the permitting of service after pregnancy. Women were also provided with more opportunities to serve overseas, including service with NATO forces in Europe and with the United Nations Emergency Forces in the Middle East.

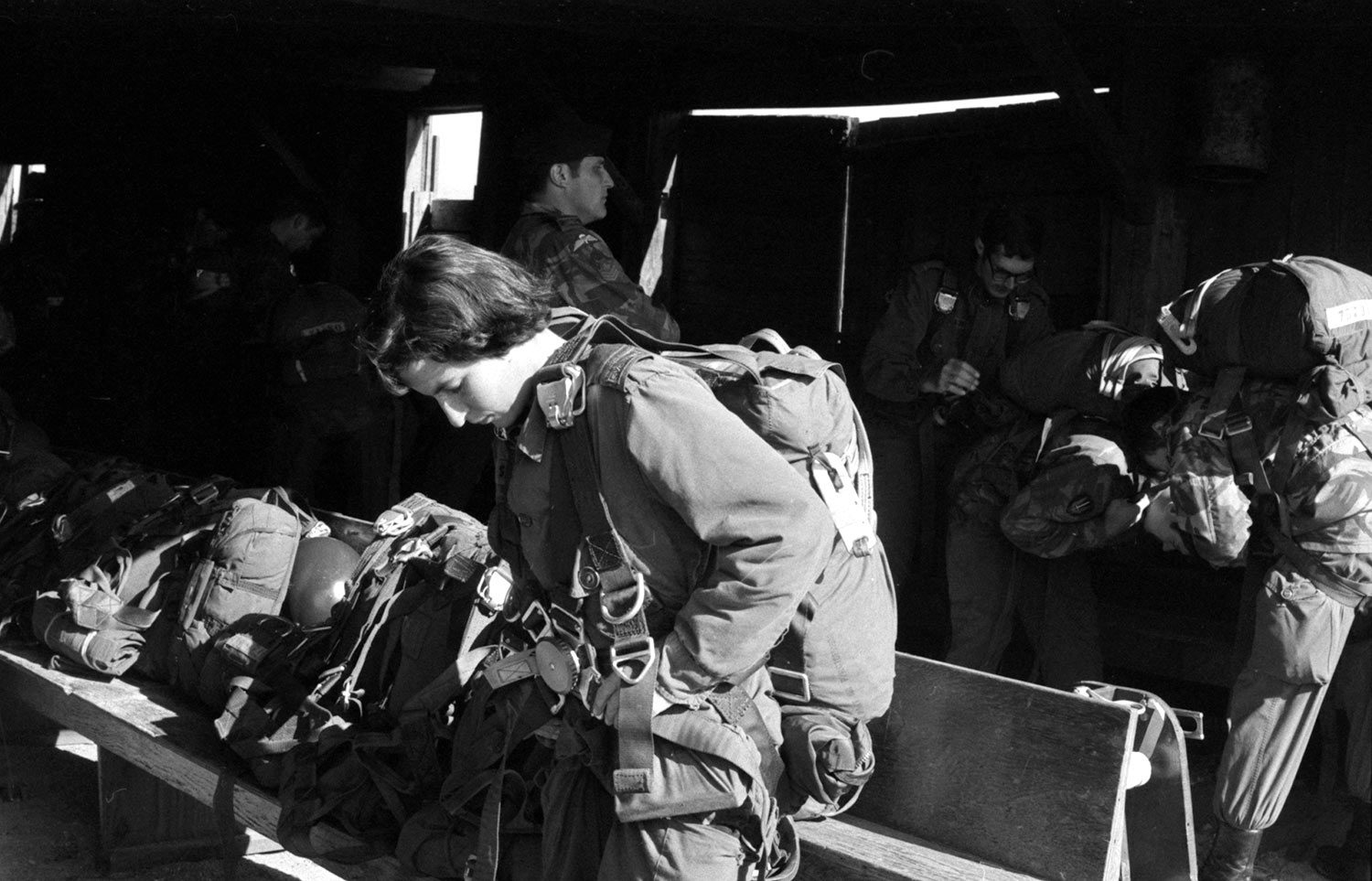

These reforms were a major challenge to the military’s patriarchal structure. But one area that the Department of National Defence (DND) hesitated to endorse was permitting women to enroll in non-civilian courses in military colleges and to serve in combat trades and occupations. Based on the Canadian Human Rights Act of 1977, the Canadian Forces were forced to re-evaluate their employment policies. The outcome was that a limited number of women were accepted into near-combat roles as part of a trial. Among the roles available in the trial were positions operating support aircraft, vehicles and ships, performing maintenance work close to frontlines, and deployment to remote areas, such as Canadian Forces Station Alert in the Arctic.

Gender barriers continued to be removed in the 1980s. In 1985, a parliamentary sub-committee recommended removing all gender restrictions in the Canadian Forces so that the military would align with the Equality Rights section of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Air Force was the only service branch to implement the recommendations immediately, while land and sea forces awaited results from their trials of women in combat roles. Before the trials could finish, the Canadian Human Rights Commission investigated complaints of gender discrimination and, on February 20, 1989, it demanded the removal of gender barriers with the exceptions of service on submarines and in the Roman Catholic chaplaincy. The DND accepted the changes and implemented the reforms by 1991.