Menu

The Upper Canada Rebellion of 1837-38

Introduction

Few anticipated that demands for political reform in Upper Canada would culminate in an armed rebellion. And yet, contextual factors, combined with the fateful decisions of those who represented the Crown and the Reform movement, made a rebellion possible. The most cited consequence of the Rebellion of 1837-38 was that it led to the Durham Report, which recommended the unification of Upper and Lower Canada and supported the Reformers’ demand for responsible government. The British government authorized the unification of the provinces under the British North America Act, 1840, but measures for responsible government passed a decade after the rebellion in 1848.

Politically, the Rebellion of 1837-38 remains an important milestone in Ontario’s history, but its impact and significance would have seemed much more immediate and profound to those enveloped by its dramatic events.

Sparking the flame

Throughout the 1830s, Reformers in Upper Canada criticized the concentration of executive power among appointed colonial administrators, whom they referred to as the “Family Compact.” In accordance with the Constitutional Act of 1791, the colonial administration of Upper Canada was headed by a Lieutenant Governor who was appointed by the British Colonial Office. Although the Constitutional Act provided for the election of representatives in the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada, the body was effectively powerless because the Lieutenant Governor could veto its legislation. The Lieutenant Governor wielded even more power because he made the appointments to the Executive Council, which advised him on governance. He also made life-long appointments to the Legislative Council (or Upper House) to debate and pass legislation in conjunction with the Legislative Assembly. In short, the power of elected representatives was more symbolic than functional, leading to the emergence of the Reform movement and its advocacy of egalitarian and democratic reforms. Among their most popular demands was the British principle of “responsible government,” whereby key governing bodies are accountable to elected representatives rather than political appointees.

Watch this video and learn more about the Family Compact.

Watch this video from Canada’s History that provides an overview of the rebellions.

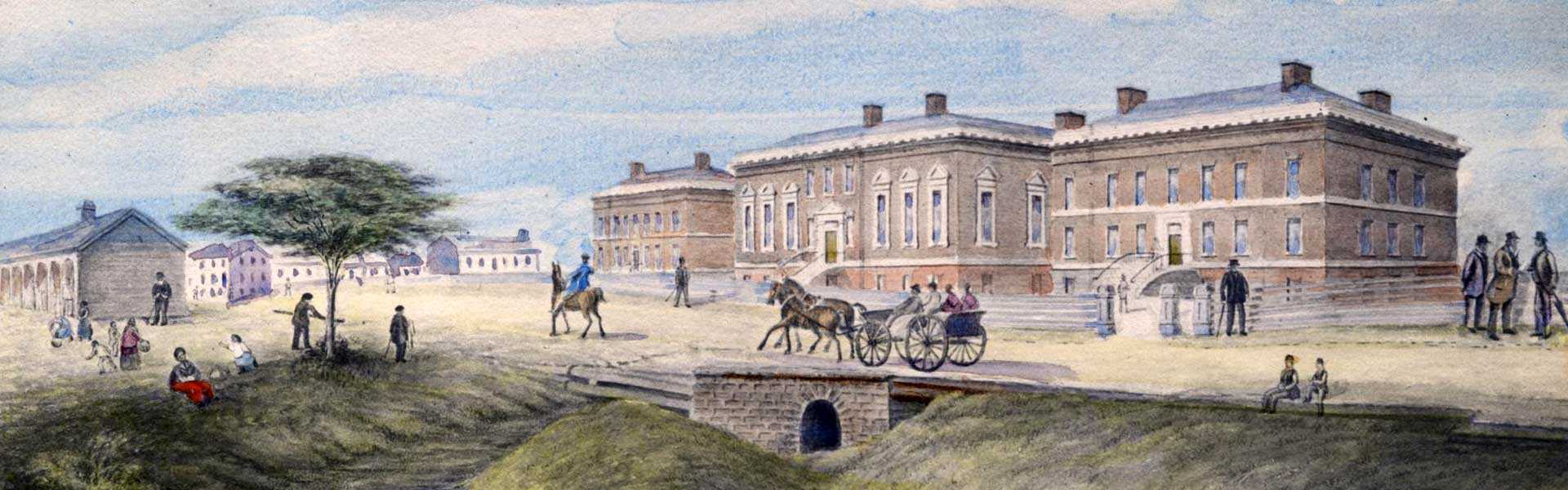

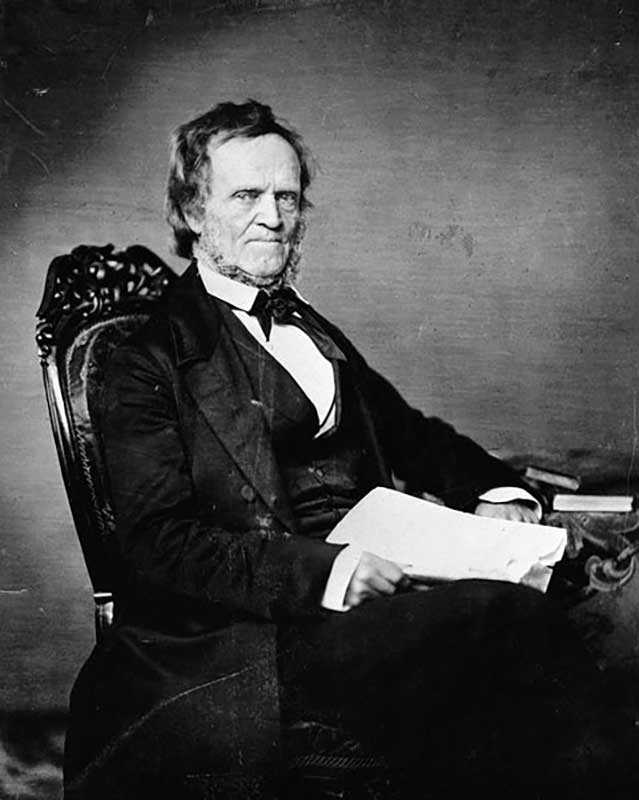

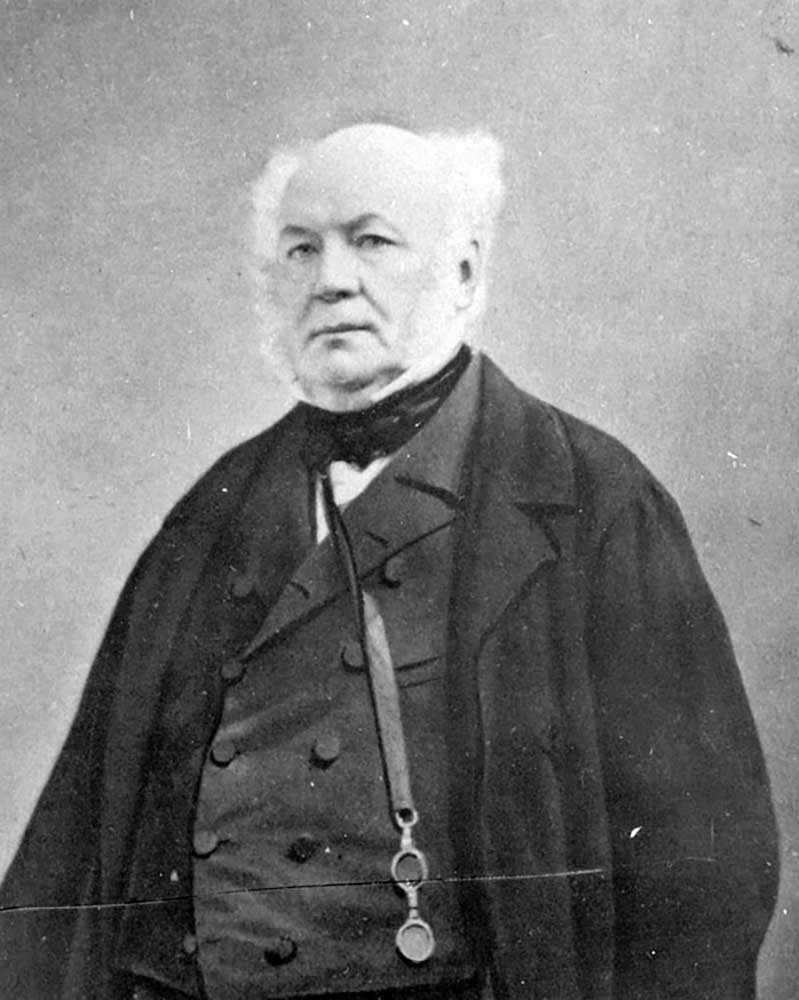

Tensions between the Reformers and colonial elites intensified in 1836. The British government initiated a half-hearted attempt to appease the Reform movement by appointing Sir Francis Bond Head as the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada. When Bond Head arrived in Toronto in January 1836, he took a step toward fulfilling his directive by appointing two moderate reformers to the Executive Council, Robert Baldwin and Dr. John Rolph. The appointments were hardly a meaningful concession, especially as Bond Head had no legal obligation to consult the Executive Council on all issues. Reformers protested by refusing to authorize money bills, but this prompted Bond Head to retaliate by dissolving the Legislative Assembly. During the 1836 election, Bond Head actively denounced reformers as treasonous republicans and rallied Tory supporters to defeat them. To the Lieutenant Governor’s delight, many Reform candidates were defeated. Among them was a leading figurehead in the radical wing of the Reform movement – William Lyon Mackenzie.

The political atmosphere of Upper Canada was electrified by the 1836 election results and Bond Head’s opposition, but that did not mean that the Reform movement immediately resorted to armed rebellion. Charles Duncombe, one of the few Reformers who succeeded during the election, carried a petition to the Colonial Office protesting Bond Head’s interference, and accused the Lieutenant Governor of electoral fraud. After Duncombe’s efforts stalled, he left politics alongside other notable Reformers, including Baldwin. Within this context of political obstruction, the idea of an armed revolt became more alluring to radical reformers like Mackenzie.

In November 1837, Mackenzie seized an irresistible opportunity. Reformers in Lower Canada staged an armed rebellion, leading Bond Head to dispatch both Upper Canada’s garrison of British regulars and Toronto’s garrison to Lower Canada. With Upper Canada lightly guarded, Mackenzie believed that he could rally enough supporters to seize the province and leverage its occupation to secure political reform. And so, shortly after the commencement of the Lower Canada Rebellion, Mackenzie took to his horse and rode up Yonge Street in Toronto to gather those willing to break the unabating reign of the Family Compact. It was the beginning of an ill-equipped and ill-planned rebellion, but as Mackenzie surely believed at the time, fortune favours the bold.

The initial uprising

By early December, Mackenzie and other rebel leaders mustered roughly between 700 and 800 armed supporters from Toronto’s surrounding counties. Most of those who he gathered were farmers, labourers and craftsmen born in North America. Women were also part of the mobilization for both sides. Although there are no records of women taking up arms, women contributed through armament preparation, such as melting lead into bullets and sharpening swords. Women also played vital roles in providing intelligence and nursing the sick and wounded. Undoubtedly, those who supported the uprising were inspired by the principles of democratic reform and Mackenzie’s leadership. But the ongoing economic recession, poor harvest, scarce money supply and prevailing grievances regarding land claims likely fuelled belligerent temperaments. Some rebels may have simply been swept up in the excitement.

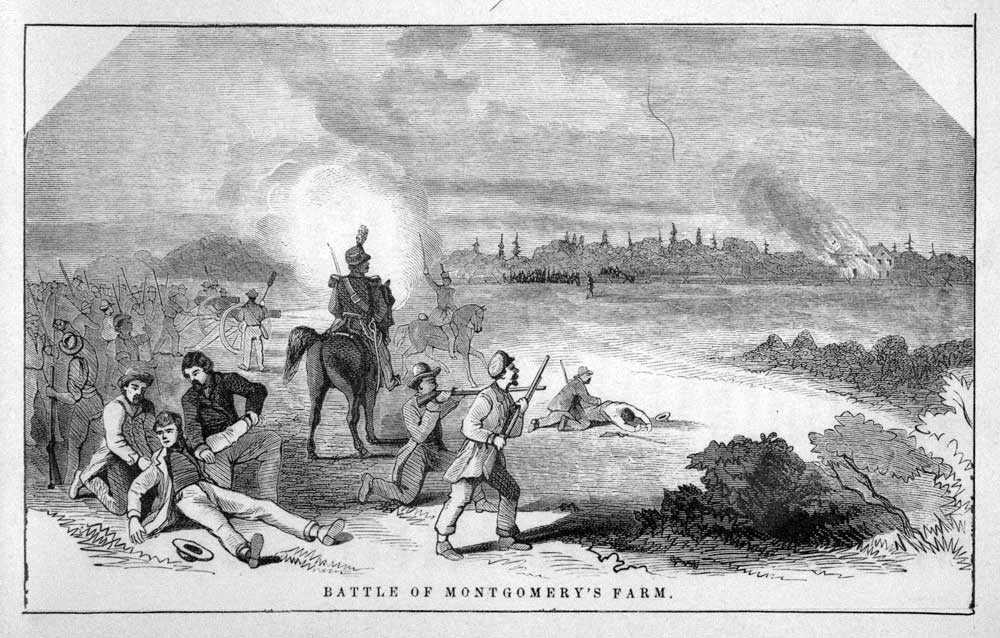

Motives aside, Mackenzie’s hastily composed regiment departed their staging ground at Montgomery’s Tavern on December 5 and marched down Yonge Street to claim the provincial capital. The challenge would not go unopposed. Mackenzie’s activities were obvious, giving Bond Head an opportunity to rally Loyalists to defend the town. Chaos ensued when the two forces clashed, but it worked to the Loyalists’ advantage. Rather than kneel or step aside, the front ranks of the rebel forces dropped to the ground to allow those behind them a clear line of fire. This non-traditional manoeuvre caused the rebels further back to believe that a Loyalist volley had decimated their entire front line. Panic ensued, and Mackenzie’s attack was broken off.

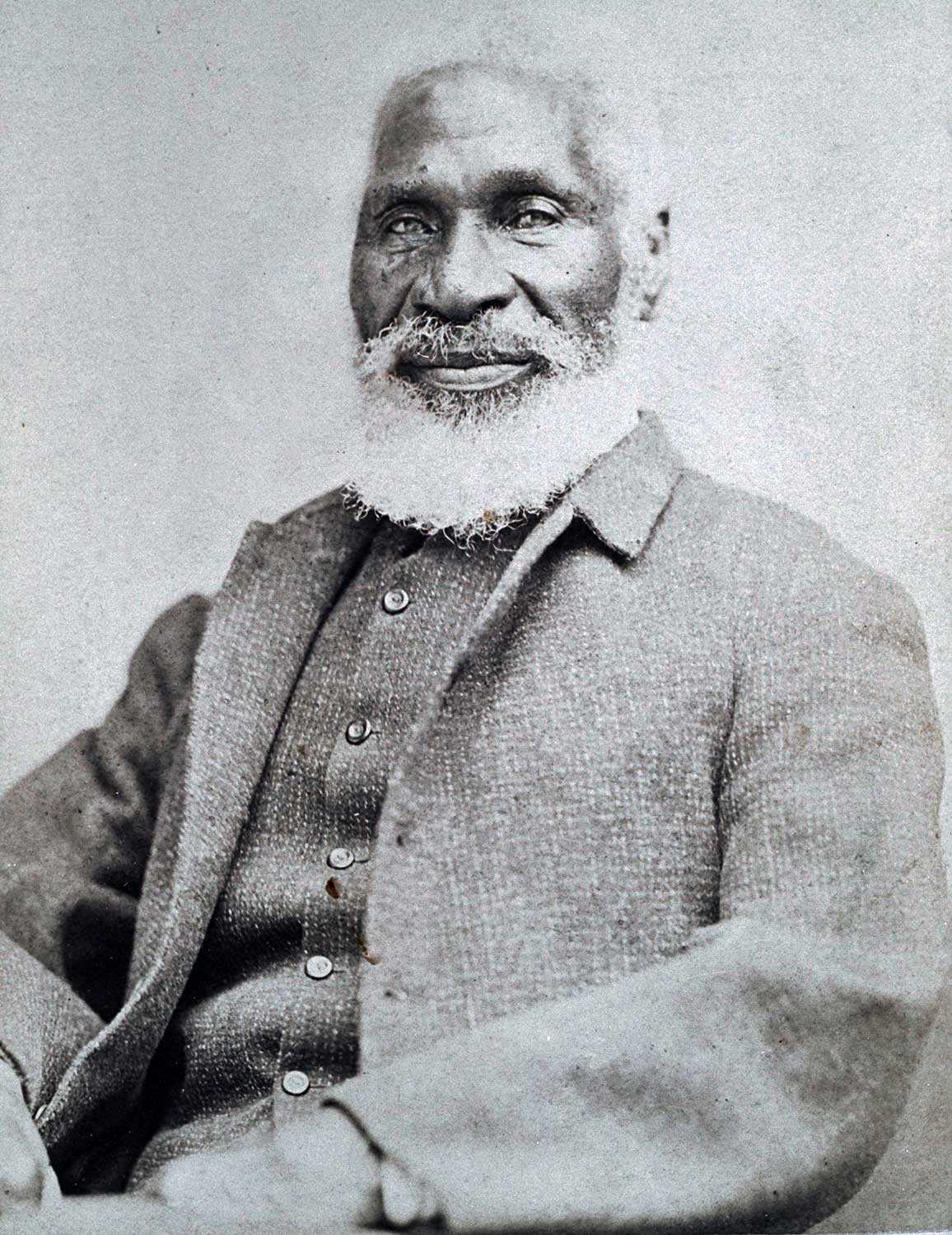

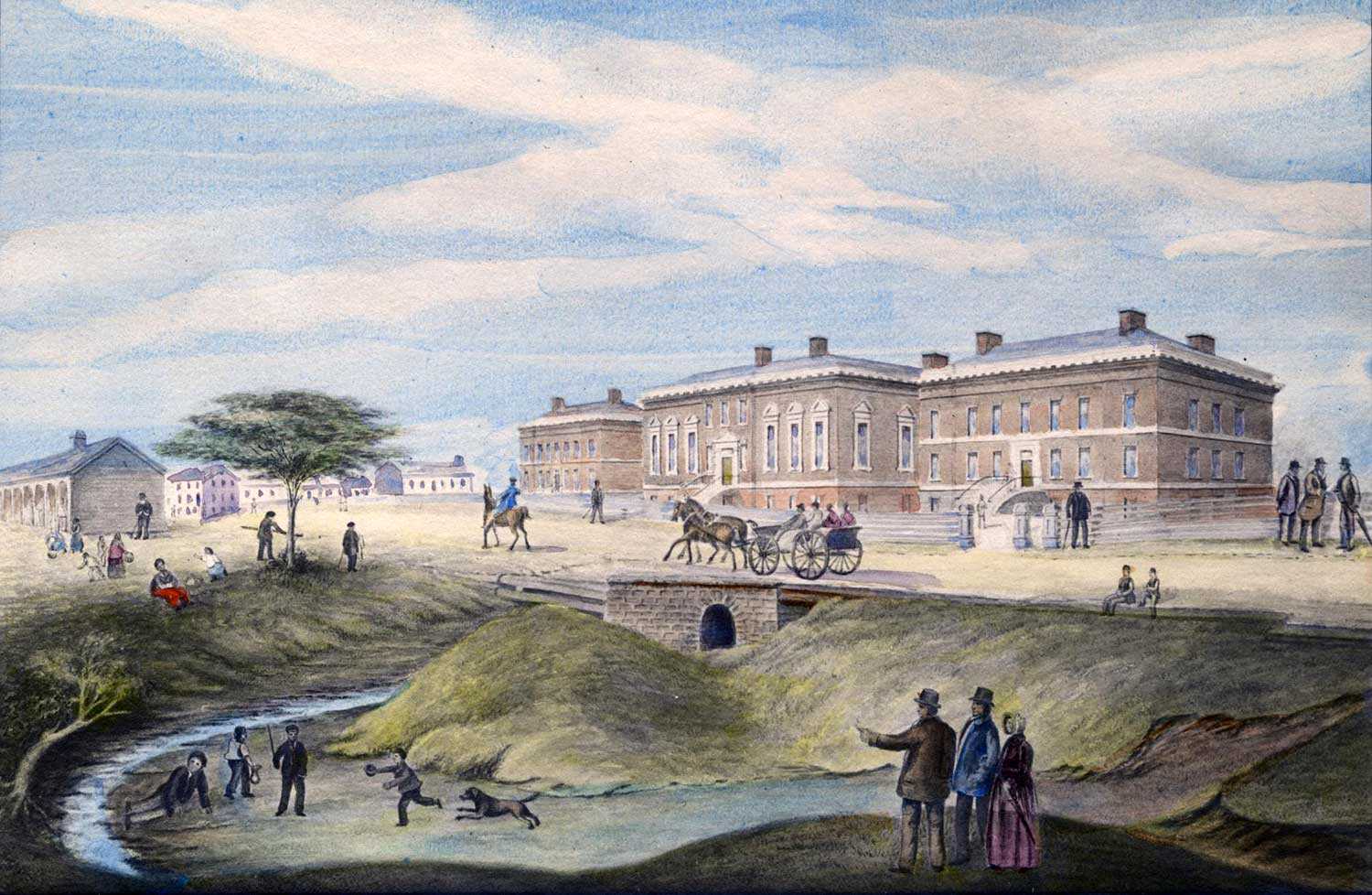

The following day, Loyalist reinforcements bolstered the city’s defences. Among them were 120 Black militia who feared that the rebellion’s triumph would usher in a Republican-style government and a return to slavery. As it currently stood in Upper Canada, slavery had been abolished since 1834 and, as of March 24, 1837, Black Canadian men were granted the right to vote. Hence, Black Canadians had more rights over their American counterparts, and Loyalist rhetoric ensured that Black men feared the loss of these advantages. Also accompanying the reinforcements was Colonel Allan MacNab, who was granted leadership over the bulk of the Loyalist forces. On December 7, MacNab assembled a force between 1,000 and 1,200 troops at Bishop’s Palace, then went on the offensive to confront Mackenzie’s army at Montgomery Tavern. The Loyalists had the advantage of both numerical strength and field cannons. Within hours, the rebel army fled, and Mackenzie along with an estimate 200 others made their way to the safety of the United States. As punishment for collaboration, the British burned down Montgomery’s Tavern. The owner, John Montgomery, was taken prisoner but later he made a dramatic escape to the United States as well. Two rebel leaders, Samuel Lount and Peter Matthews, were not so fortunate. After being captured, Lount and Matthews were publicly hanged on April 12, 1838. Their bodies were buried at Potter’s Field near the intersection of Yonge and Bloor.

The defeat of the Patriots at Montgomery’s Tavern dealt a crushing blow to Mackenzie’s ambition of seizing Toronto, but Loyalist forces still had to contend with a second uprising in Upper Canada’s western counties. While Mackenzie rallied forces to attack Toronto, a false rumour spread that Mackenzie had already succeeded. Charles Duncombe, who had no preceding indication that the Reform movement was staging a rebellion, was swept up by these events. He was also alarmed by information that Bond Head had pre-emptively authorized his arrest. Feeling both threatened by the prospect of incarceration and encouraged by the news of Mackenzie’s success, Duncombe decided to embrace the armed revolt from the London District. Historical estimates place the size of Duncombe’s army as roughly 400 strong. Most of the rebels were from Norwich and Oakland, and to a lesser extent, Yarmouth, Dereham, West Oxford, Blenheim and Dumfries townships. But as fast as Duncombe felt momentum building on his side, it shifted against him. On December 13, Duncombe learned that Mackenzie was actually defeated and, moreover, that MacNab’s Loyalist army was approaching from nearby Brantford. To make matters worse, MacNab’s army received additional reinforcements as he marched southwest, including 100 Indigenous warriors from the Six Nations on the Grand River Tract. The following day, Duncombe’s army began to disperse. Duncombe and other rebels fled to the United States to regroup and to escape arrest. And so, the second rebel army was defeated without a major confrontation. MacNab stood in triumph, but unbeknown to him, the “Patriot War” was just beginning.

Border raids in the Patriot War

Fears of subsequent uprisings in the western counties led many western townships to be temporarily occupied by militia companies. The border was also reinforced with numerous companies, including companies of Black Canadians from Chatham, Sandwich, Hamilton, Niagara, St. Catharines and Toronto. In addition to the presence of military units throughout the colony, draconian legislation was passed in Upper Canada to allow for the prosecution of those suspected of direct or indirect involvement in the rebellion, while those acting in a capacity to suppress the rebellion were given legal immunity.

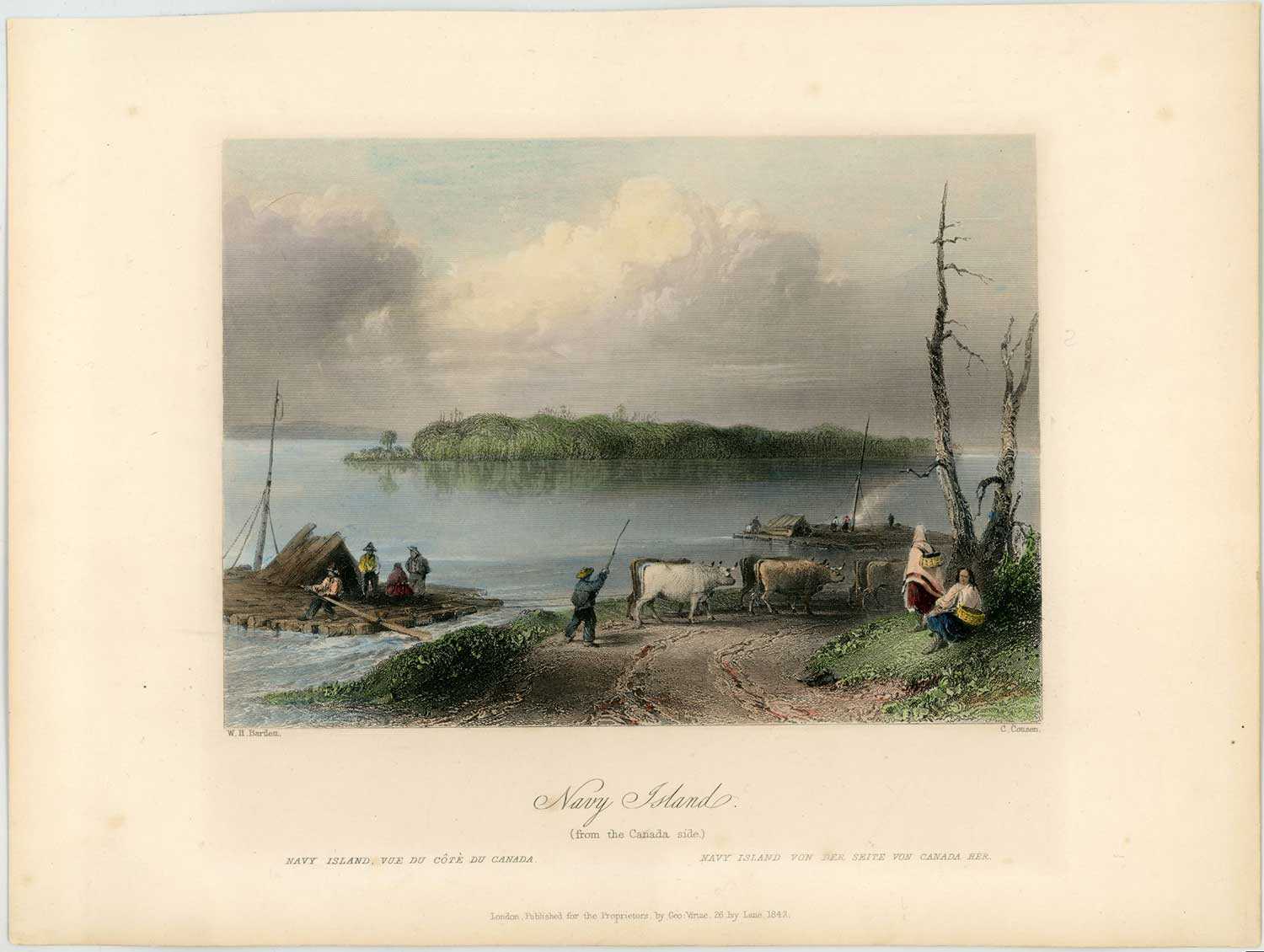

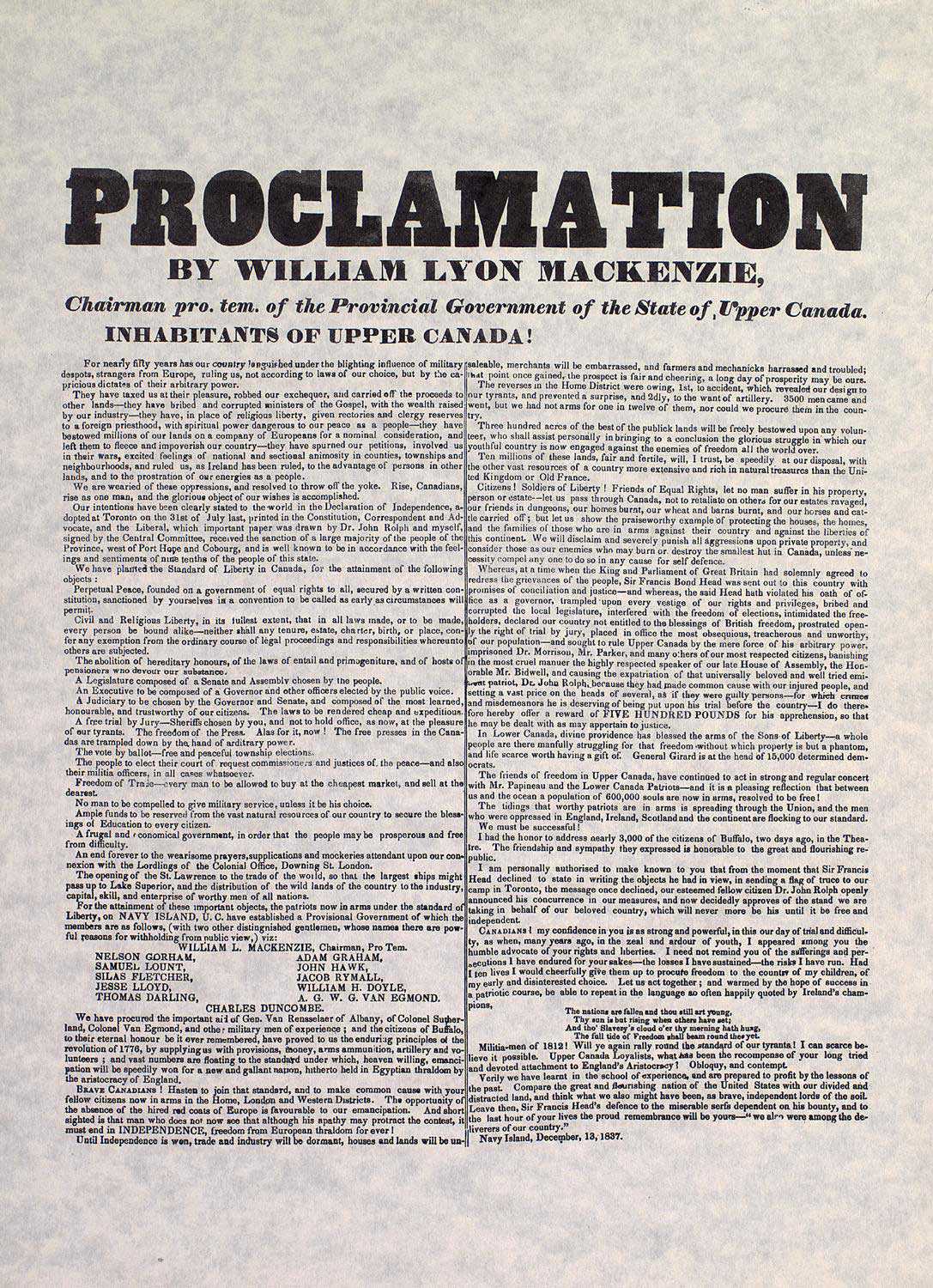

On the American side of the border, Mackenzie and his fellow Patriots received a warm reception when they arrived at Buffalo on December 11, 1837. Americans applauded their bold defiance of the British Crown for reasons ranging from historical grievances to recent beliefs that English banks caused the ongoing recession. Military romanticism also thrived in the wake of the Texas Revolution. Strengthened by American support and volunteers, Mackenzie contemplated his next move. Under the Neutrality Act, Mackenzie could not wage war from within American territory, so it was decided to occupy Navy Island on the British side of the Niagara River.

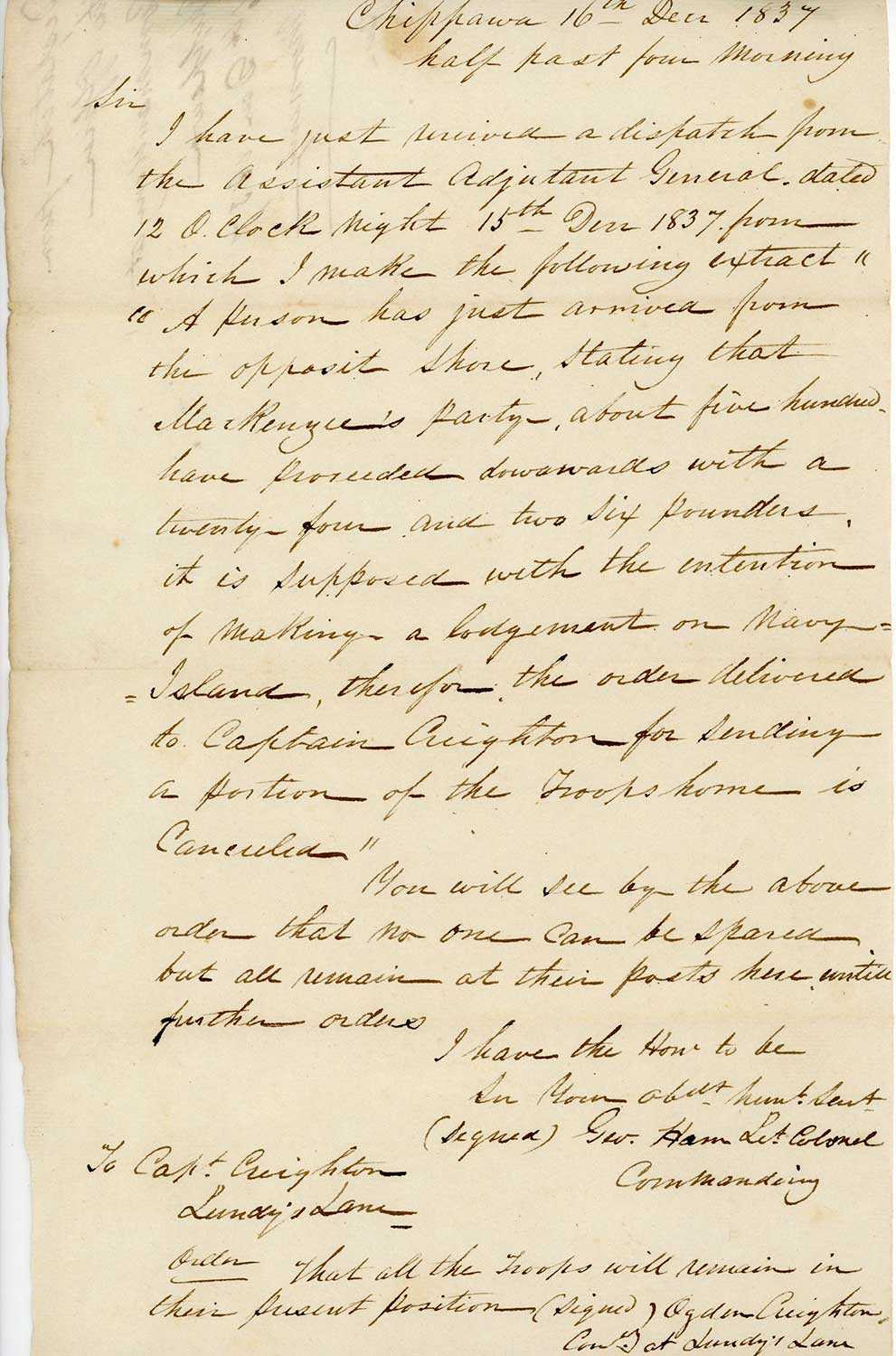

On December 14, Mackenzie set up camp on Navy Island. He was accompanied by Stephen Van Rensselaer (the descendant of General Van Rensselaer of the War of 1812) and two dozen volunteers. Over time, volunteers from both sides of the border increased the Patriots’ strength on the island to be between 450 and 600 occupants. The occupation drew the attention of the American authorities, leading to Mackenzie’s arrest. He was released on bail, however, and then returned to the island. MacNab responded to the occupation by deploying roughly 2,000 soldiers on the Niagara border, including hundreds of allied Indigenous warriors. Rather than assault the island, which was reinforced by cannons, MacNab instructed Captain Andrew Drew and 60 Upper Canadian militia to dispose of the rebel’s supply ship. On December 29, Drew captured the Caroline at the American port of Fort Schlosser on the Niagara River. After taking control, he set the ship on fire, steered it down the river towards the Niagara Falls, and then abandoned it to its destruction. With a lack of supplies and facing harsh winter conditions, the Patriots’ morale withered away and they abandoned the Navy Island in defeat. MacNab’s plan succeeded but “the Caroline Affair,” as it came to be known, had the unintended consequence of enraging the American populace. After all, MacNab had technically violated American territorial sovereignty and destroyed an American ship. In this way, the occupation of Navy Island ended but American zeal to support the Patriots intensified.

As the Patriot War entered the new calendar year, the incursions onto British border islands continued. The Patriots occupied the island of Bois Blanc on the Detroit River. The Patriot schooner, the Anne, came under heavy fire and ran aground at Elliott's Point on January 8. Josiah Henson, who would later become one of the famed “Conductors” of the Underground Railroad and founder of the Dawn Settlement, was among those who assaulted the ship. Fighting at his side were 50 Black Canadian volunteers who succeeded in capturing the Anne’s crew and cargo. Similar to Navy Island, the Patriots soon abandoned Bois Blanc because of inadequate logistical support. Later in February, Duncombe assisted the preparations for another Patriot occupation on the Detroit River. This time they chose Fighting Island. But once again, the Patriots’ lack of supplies forced them to retreat.

The Patriot attacks continued despite their repeated failures. In late February, 300 Patriot soldiers moved across the ice of Lake Erie to occupy Pelee Island. On March 3, British regulars, Upper Canadian militia and Six Nations warriors confronted the Patriots during the Battle of Pelee Island. At this battle, 11 Patriots were killed, 44 wounded and another 11 taken prisoner. The British forces suffered 25 wounded and five killed. Van Rensselaer led another occupation south of Gananoque on Hickory Island. The initial force was only 50 strong, but it may have increased to a peak of 300. The occupation was intended to be a staging ground to raid Gananoque and attack Kingston, which was undefended at the time. Elizabeth Barnett, an American teacher who resided in Gananoque, visited family near Clayton, New York. Barnett was overwhelmed by the Patriots’ highly visible preparations, leading Barnett to race back home and warn British authorities. Lt.-Col. Richard Bonnycastle was already aware of the invasion, however, through his intelligence network and counter-measures were underway. Doomed to failure, the Patriot occupation on Hickory Island dwindled. When Bonnycastle and his militia forces moved to apprehend the Patriots, he met no resistance and arrested 50 Patriots advancing on Kingston. American authorities later arrested Van Rensselaer.

During the Spring and Summer of 1838, the Patriot War lost some momentum, but it continued. Appreciating the need for greater secrecy, the remaining Patriot leaders established Hunters’ Lodges, which operated as secret societies. Most were located near the American-Canadian border. For the most part, Hunter Patriots focused on consolidating their forces in preparation for a major assault at the end of the year, but there were some daring initiatives undertaken to secure supplies and allies.

One covert operation involved the infamous and elusive “Pirate” Bill Johnston – a former Loyalist who turned to smuggling and piracy during the War of 1812. On May 30, 1838, Johnston and “General” Donald McLeod led a small group of Hunter Patriots onto the British steamboat, the Sir Robert Peel, while it was docked at French Creek in the Thousand Islands area. After looting the ship and its passengers, Johnston’s crew failed to start its engine. Since they could no longer steal the ship to use as a ferry for Patriot troops, they decided to burn it in revenge of the Caroline. The attack drew the attention of the American authorities. Johnston’s crew was later arrested, but Johnston evaded the authorities on both sides of the border by hiding in the Thousand Islands.

A second noteworthy incursion was the Short Hills raid. On June 10, 1838, James Morreau of Pennsylvania led a small party of Patriots into the Niagara Peninsula, who were later joined by sympathetic residents. Their mission was to convince the Six Nations to join the rebellion. The Patriots changed their plans, however, to opportunistically ambush a group of militia cavalrymen from the Queen’s Lancers. The Lancers were apprehended, disarmed and freed into the woods, but to the Patriots’ dismay, other militia units became aware of their incursion. Ironically, the Six Nations warriors helped the British apprehend the raiders as they attempted to flee to the United States. By the end of the summer, the Patriot War was failing to make any meaningful inroads.

The Battle of the Windmill and aftermath

On November 12, 1838, the Hunter Patriots launched their major offensive to capture Fort Wellington in Upper Canada. It would mark the crescendo of the Patriot War. From the outset, the operation floundered. The offensive did not have the element of surprise as expected. Instead, the two schooners carrying the Hunter Patriot troops were fired on as they approached Prescott Harbour in Upper Canada to disembark. The flustered Colonel Nils von Schoultz broke off the landing and ordered the ships to cross to the other side of the St. Lawrence River to Ogdensburg. As the ships approached the American shore, they hit a shoal and became stranded. Johnston, being an experienced river pirate, freed one of the ships by unloading its cargo. As efforts were underway to free the second ship, Schoultz led a small party of troops downriver to Newport in Upper Canada. Once disembarked, the Hunter Patriots occupied a six-storey mill overlooking the river from a cliff. The mill had fortress-like qualities, standing 18.3 metres (60 feet) high with 1.2-metre-thick (four-foot-thick) stone walls. The residents of Newport fled, and roughly 200 Hunter Patriots occupied the mill and Newport buildings.

The first British unit to challenge the Hunter Patriots was a lone single-engine steamer called The Experiment. It was led by captain Lt. William Newton Fowell. Although the ship was only armed with an 18-pound cannon and a three-pound swivel gun, The Experiment repeatedly attacked the Hunter Patriot vessels, including a large steam vessel, the United States, which the Hunter Patriots stole from an American port. The Hunter Patriots’ naval superiority was short-lived because American authorities arrived and impounded their vessels. Moreover, two British steam vessels joined The Experiment in occupying the St. Lawrence River. On November 13, the British ships began bombarding the dug-in Hunter Patriots, who returned fire with cannons mounted in the mill. The bombardments from both sides had little effect.

On November 13, British forces composed of approximately 500 to 600 soldiers from the Grenville, Dundas and Glengarry Militia, as well as 100 British Regulars from the 83rd Regiment of Foot, arrived at Newport and assaulted the dug-in Hunter Patriots. A furious battle ensued with sniper fire from the mill, cannons firing from land and sea, and hand-to-hand combat. Tragically, a Newport family who had not yet fled attempted to escape during the battle and were fired on. Mrs. Benden Taylor, her daughter and her infant child were killed. It is unclear which side fired on the family. Ultimately, the British attack was called off, and the standoff resumed.

During the third day of the siege, the British forces were reinforced by 300 British regulars, 600 Canadian militia, a company of veteran Highlanders and two18-pound cannons. After Schoultz refused to surrender unconditionally, the British artillery commenced their bombardment. Surprisingly, cannonballs ricocheted off the mill. The less durable buildings of Newport were not as resilient, and the bombardment turned the village into rubble. As the British and Canadian forces began systematically burning the ruins to flush out snipers, the Hunter Patriots finally surrendered. The British regulars were forced to escort the prisoners to safety because many Canadian militia demanded their immediate execution.

The official statistics regarding the casualties on both sides remain controversial. Official records claim that as few as 13 British and Canadian troops were killed and 69 wounded, but Hunter Patriot accounts indicate that the number of fatalities may have been in the hundreds. Estimates for the Hunter Patriots’ casualties also range widely and were somewhere between 17 and 50. Colonel Schoultz, the commander of the Hunter Patriot campaign, was hanged at Kingston on December 8, 1838.

The Battle of the Windmill marked the climax of the Patriot War in Upper Canada, but the final blow came on December 4. A Patriot army launched another offensive across the Detroit River and occupied the town of Windsor. Colonel John Prince led the local Upper Canadian militia into battle. Prince emerged victorious in the Battle of Windsor, and the Patriot War came to an end.

For some Patriots, however, it was not easy to admit defeat. As late as April 17, 1840, Brock’s Monument, which commemorated the heroism of Major General Sir Isaac Brock during the War of 1812, was destroyed by a bomb. Many suspected that the sabotage was by former Patriot Benjamin Lett. Although it took nearly two decades, the monument was reconstructed.