Menu

Ontario's wartime economy

Introduction

In August 1914, the people of Ontario were coping with a major recession. The onset of the Great War further compounded pre-existing hardships because access to British credit was suspended, stock exchanges closed, Atlantic shipping ceased and public fears led to a rush of gold withdrawals. Gradually, international and national efforts restored economic stability, and the financial shock of going to war dissipated. Not only did Ontario’s economy slide out of a recession, but by mid-1915, many sectors entered a period of economic growth, prosperity and innovation. This section examines some interesting stories, highlighting Ontario’s collective efforts to mobilize its resources and ingenuity. It also highlights how wartime prosperity led to agitation against wartime profiteering.

Wartime production

Following the outbreak of the war, Lord Kitchener, the British Secretary of State for War, instructed the Canadian Militia Department to purchase military supplies in the United States on his behalf. The Minister of Militia and Defence, Sam Hughes, complied, but sensing opportunity, he also convinced Lord Kitchener to place additional orders in Canada. Gradually, Canada’s manufacturing sector (heavily concentrated in Ontario) shifted from virtually no munitions production to supplying one-third of the ammunition and half the shrapnel used by British forces. In more specific terms, Canada’s exports of shells to Europe rose from 3,000 in 1914 to nearly 24 million in 1917. It was a major industrial achievement under deplorable circumstances.

Many of Ontario’s largest industrial plants expanded to facilitate this boom. For instance, Algoma Steel in Sault Ste. Marie and the Steel Company of Canada in Hamilton doubled their steel output. In addition to expanding pre-existing facilities, public and private interests created hundreds of new manufacturing establishments and industrial complexes. As seen below, the British Chemical Company in Trenton, was among the complexes funded by the British government. It included 204 buildings across 101 hectares (250 acres), 11.3 kilometres (seven miles) of railways, and 2,500 men and women working one of three eight-hour shifts. Even Ontario’s shipbuilding industry expanded. New orders for military and merchant ships necessitated new shipyards at Bridgeburg, Welland and Midland. By 1916, shipyards at Toronto, Collingwood and Port Arthur were equipped for building steel ships.

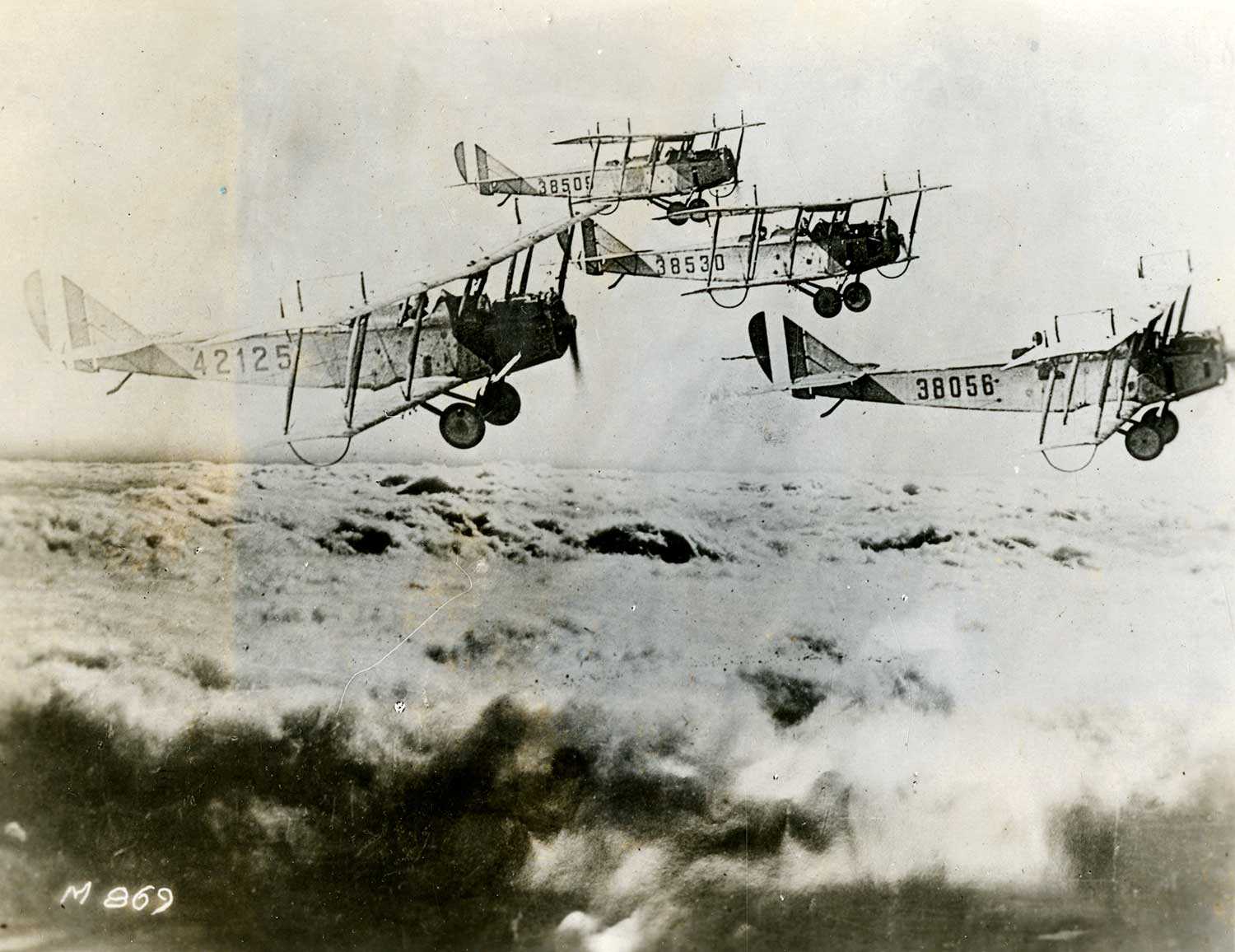

Ontario also became home to the emerging aircraft industry. In December 1916, the British government approved Canada to undertake pilot training and airplane construction. The Imperial Munitions Board (IMB), the Canadian branch of the British Ministry of Munitions, immediately purchased a small airplane manufacturing company in Toronto called Curtiss Aeroplanes and Motors Ltd. The primary reason for its acquisition was to appropriate its machines for training. For larger-scale production, the IMB promptly constructed new facilities, including a new manufacturing complex for Canadian Aeroplanes Ltd. Only months after construction started in February 1917, several large buildings were erected across 2.4 hectares (six acres). The factory was successful and produced 2,900 JN-4 aircraft over 21 months. Ontario also became home to numerous aerodromes. The first was located at Camp Borden and had 15 flight sheds and additional buildings – some of which still exist and are now designated federal heritage sites.

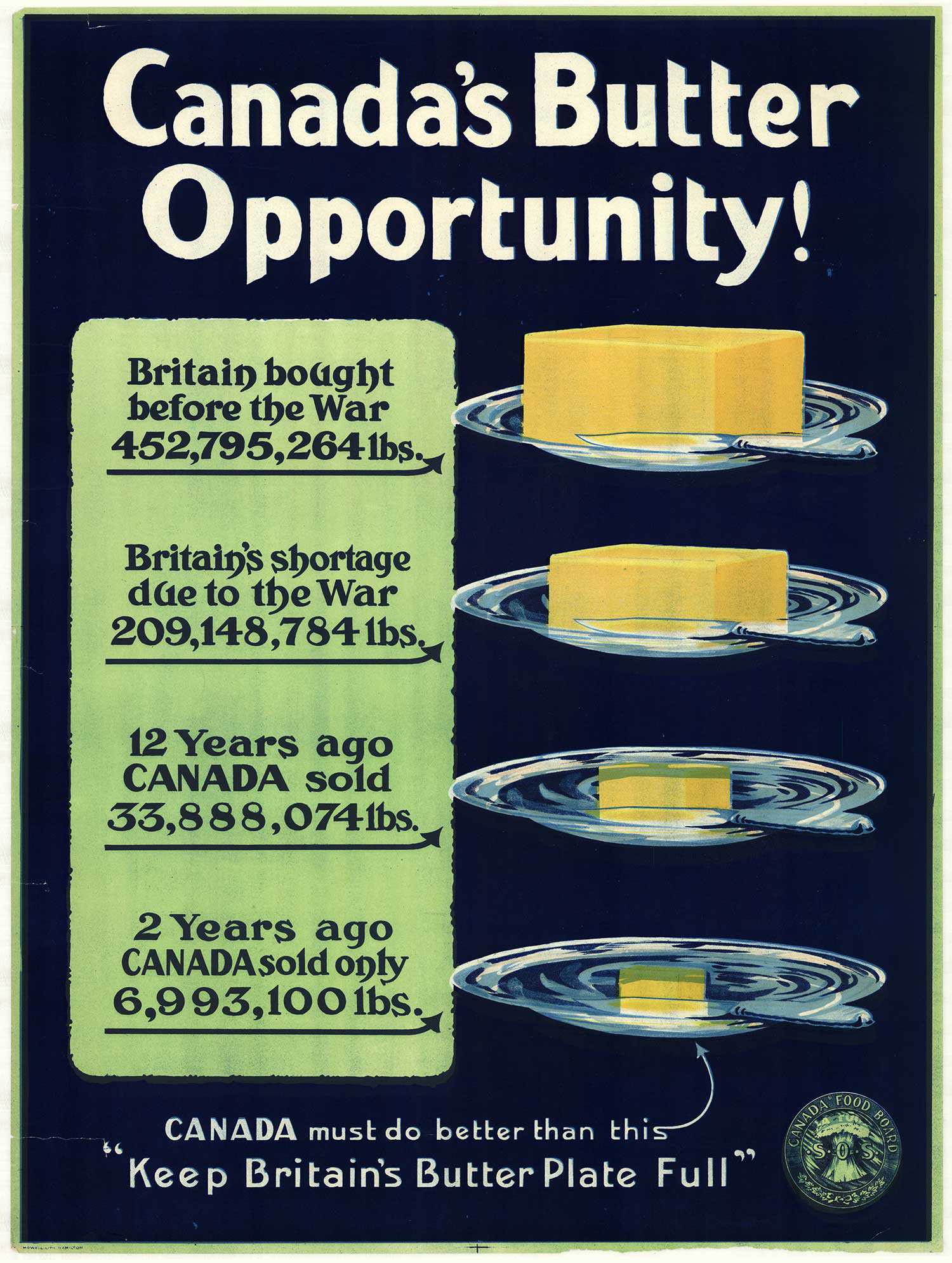

Ontario is often remembered for its wartime manufacturing, but it is important to recognize the province’s contributions to the Allied war effort through food exports. At the outbreak of the war, Britain lost access to sources of food produced in Continental Europe. The German military attempted to exploit this weakness and starve Britain out of the war by using their submarines to sink merchant vessels.

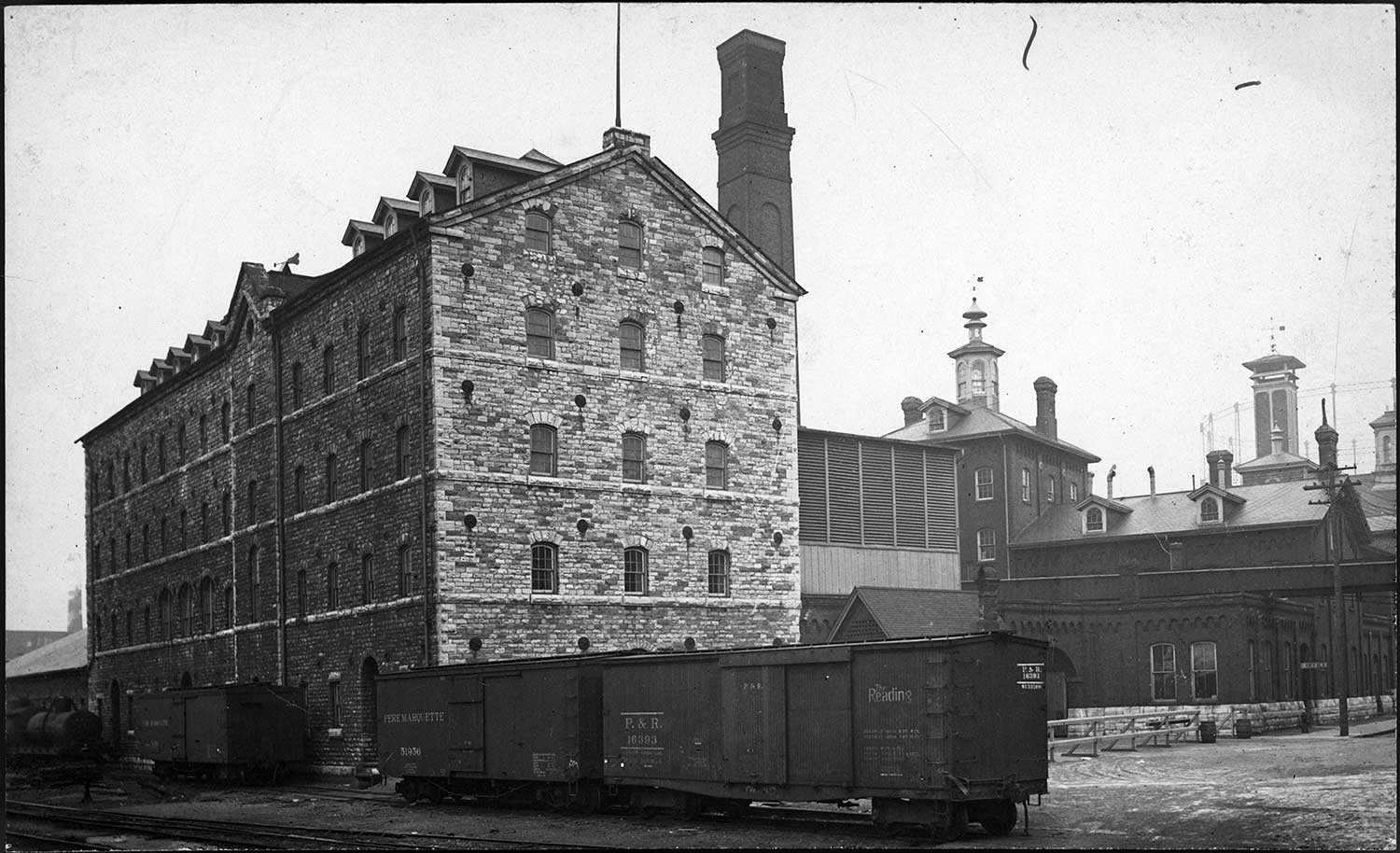

With food shortages in Britain, Ontario’s food production became critical to the overall war effort. In 1914, more residents in Ontario worked in agriculture than in factories. Their hard work earned the praise of Ontario’s Premier William Hearst, who stated, “The farmer at work in the field … is doing as much in the crisis as the man who goes to the front.” But more than honouring the farmer with recognition, the provincial government provided local farmers with educational resources, 1,000 tractors at cost and loans to purchase additional seeds. As demand for food overseas intensified in 1916, prohibition was enacted to prevent crops from being used to produce alcohol. Distilleries, such as the Gooderham distillery in Toronto, shifted production from whisky to chemicals and compounds needed for war production, such as acetone and cordite.

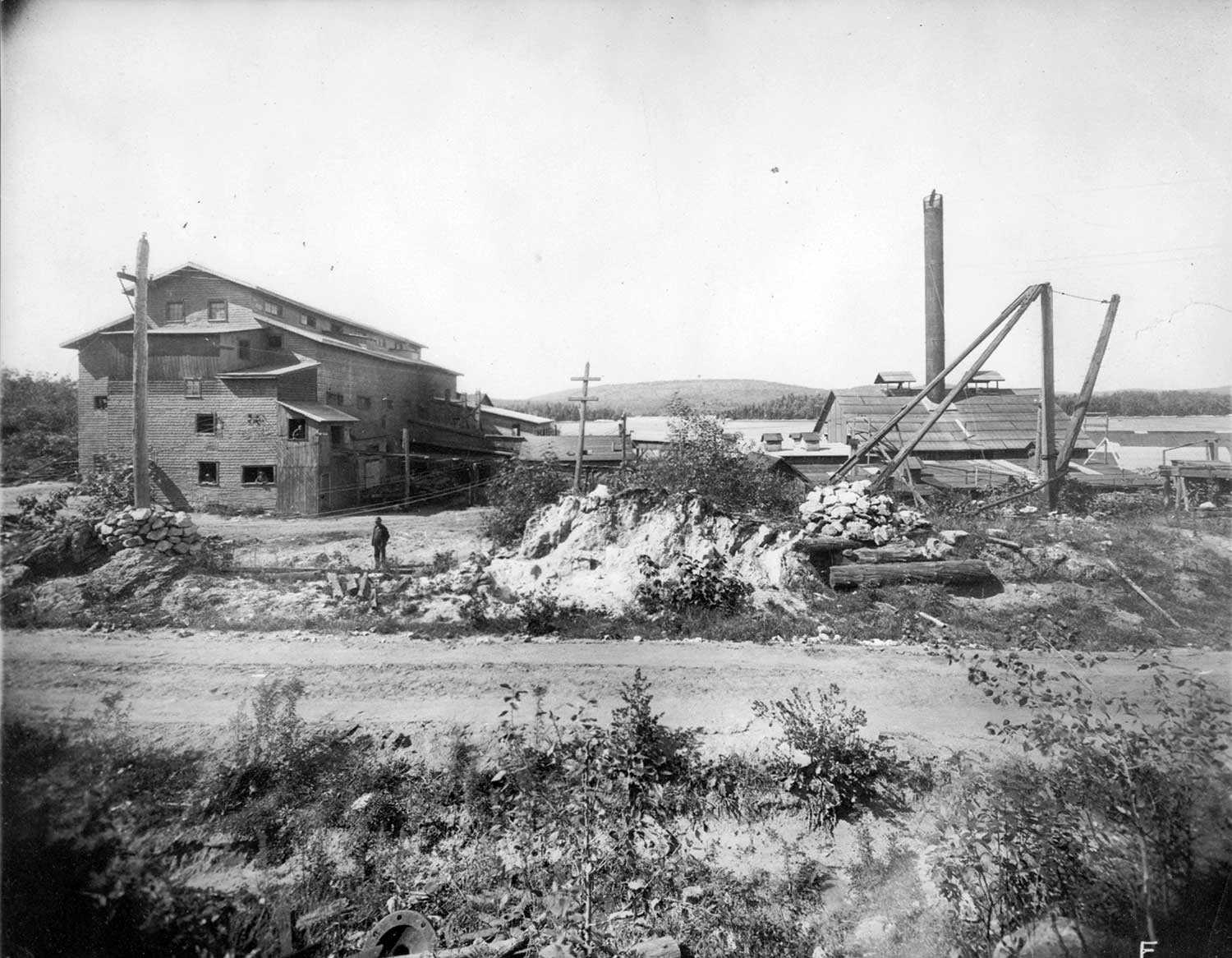

Resource extraction in Ontario was similarly crucial for the war effort. Workers extracted key materials for military production, including iron, sulphur, zinc and copper. For example, The Black Donald Graphite Mine reached peak production during the war and provided 90 per cent of Canada’s graphite.

Arguably the most critical resource extracted in Ontario was nickel. The Sudbury region accounted for approximately 80 per cent of the global nickel supply before the war. Nickel was important for war production because it was an essential ingredient in hardened and chromed steel. Controversy arose in late 1914 and 1916 when reports reached Canada that German submarines purchased hundreds of tons of Canadian-mined nickel from American refineries. A Royal Commission later recommended that the government provide funds to construct privately owned nickel refineries within Canada. But by the time the refineries were operational, the war was nearly over. Nevertheless, Ontario’s war, food and resource production were significant contributions to the Allied war effort.

War production and women

In the early 20th century, opportunities for women to work in the labour force were highly restricted. Once they got married, women were expected to leave their jobs to assume the full-time and unpaid positions of managing the household. Married women were also legally restricted from owning property at the time. It was difficult for women to challenge these norms because even the labour movement, which was still dominated by male trade unionists, were fierce opponents of female labour. As most male trade unionists believed, women threatened male wages and male breadwinning status. Facing legal restrictions, widespread social prejudice and organized opposition, women had access to only a limited number of wage-earning opportunities. Most of these jobs were concentrated in domestic service, light manufacturing (consumer goods and textiles), clerical work and the service sector. With the onset of the Great War, however, male labour became increasingly scarce. These conditions led to the relaxation of gender norms and increased government support for mobilizing female labour until the war was over.

As the war dragged on, labour shortages became acute in all sectors, including war industries. In summer 1916, the Imperial Munitions Board appointed Mark Irish, a member of the Ontario legislature, to investigate the possibility of employing women in munitions plants. The task was considerable because most manufacturers were reluctant to employ women in heavy industries. Prevailing stereotypes about women led employers to believe that women lacked the necessary work ethic. As a result, employers were unwilling to incur expenses for women’s special accommodations, and they feared reprisal from their male employees who were guarded against female encroachment. Nevertheless, Mark Irish and other Labour Department officials pressed on in their campaign to recruit women into munitions factories and other industrial plants. Sometimes, they collaborated with women’s organizations to ensure a smooth integration, including overseeing the construction of women’s canteens and living quarters.

Between mid-1916 and the end of the war, women endured extremely tough working conditions in the war industries. In addition to exhausting 12-hour shifts (or longer), women had to tolerate extremely hazardous working environments. For instance, the Toronto Globe and Mail reported that six workers were killed and eight seriously injured when a pile of cordite accidentally ignited from a spark at the Canadian Explosives Limited plant in Montreal. Among the survivors that required hospitalization were Bettina Lacasse and Laura Eil. Since industrial accidents such as these were published in newspapers, women were aware of the dangers that munitions work entailed. Yet, women volunteered regardless. By the war’s end, 35,000 women had been employed in munitions factories.

Undoubtedly, women had proven themselves as capable industrial workers, earning the gratitude of figureheads like Mark Irish. Despite the respectability of these wartime contributions, however, the acceptance of women’s employment in heavy industries was endorsed by the government as a last resort. Following the armistice, government officials, employers and male-dominated unions colluded to remove women from heavy industries so that it did not threaten the labour market’s patriarchal structure.

Thrift and profit

Between 1913 and 1920, the average price of food staples in Canada increased by nearly 150 per cent. These price increases can be attributed directly to the war. Firstly, the war shifted tens of millions of people from their productive occupations into the work of destruction – both in the sense of becoming soldiers and as workers supporting the military. Secondly, belligerent governments adopted loose monetary policies to fund their war efforts, leading to inflation. With a shrinking global supply of food and an increasing supply of money, food prices skyrocketed.

Food scarcity and soaring prices made life difficult for low-income households in Canada, but overseas, in Great Britain and France, food shortages were severe enough to warrant nationwide food rationing. In response, Canadian politicians and state officials called upon the people to “do their bit” by conserving food so that more would be available for export.

Ontario’s thrift and conservation campaign began in April 1917. State officials co-ordinated their efforts with civil organizations, such as the National Council of Women of Canada and the Imperial Order of the Daughters of the Empire. Together, they opened “thrift centres” to offer the public educational material and classes on food substitution, food preparation, backyard gardening and general consumption strategies. The food conservation campaign also encouraged the public to commit formally to food substitution and conservation strategies by signing pledge cards. For example, the public was instructed to observe designated “meatless days.”

While patriots followed guidelines for food conservation and thrift, food profiteers exploited wartime conditions for profit. The most notorious food profiteer was Toronto’s highly successful meat packing magnate, Joseph Flavelle. The so-called “Bacon Baron” was catapulted into the spotlight after the Cost of Living Commissioner reported that the William Davies Company’s exports had increased dramatically during the war. As the largest shareholder of the William Davies Company, Flavelle was said to have netted $1,685,345 in dividends between 1914 and 1917. Earning such a massive fortune while Canada’s soldiers risked their lives for only $1.10 a day was a moral outrage to many. Other aspects added to the debacle. Firstly, Flavelle served as the Chair of the Imperial Munitions Board, a crucial and prestigious position in the Allied war effort. Secondly, he received a baronetcy in 1917 for his wartime service. And, thirdly, on returning from Europe, he gave a speech famously proclaiming, “to hell with profits!” Flavelle’s excessive profits came in sharp contrast to his patriotism, leading pundits across the country to call for his dismissal, if not his arrest. But, despite public opinion united against him, the British War Office and Canadian Prime Minister Sir Robert Borden stood behind Flavelle, believing that his service was indispensable.

Wartime food profiteering brought into focus the need to regulate the moral boundaries of profit through new taxation and price regulation measures. As these measures failed to live up to their promise, wartime disillusionment became widespread, leading to the election of Independent Labour and United Farmers candidates during the 1919 Ontario provincial election. The Independents won enough seats that they formed the Farmer-Labour Drury government. It was a shocking victory that inspired similar independent political action across Canada.