Menu

Schools and students at war

Introduction

Public schools, colleges and universities are widely recognized as establishments of learning and accreditation. During the Great War, however, schools in Ontario were mobilized for the war effort. School grounds were repurposed as sites for drills, military experiments and rehabilitation centres for returned soldiers. Some schools also incentivized their students to enlist and allowed their campuses to become recruitment grounds. Exploring the role of schools in Ontario highlights how the Great War led to the province’s total mobilization. It also brings into focus how children and young adults became participants in the war rather than bystanders.

Recruiting students

As early as October 1914, teachers from the University of Toronto (then a provincially controlled school) promoted the war’s legitimacy through a lecture series explaining the war’s origins. The lecture series was instantly popular and drew an average audience of 800 people per event.

School administrators were also interested in galvanizing support for the war effort. By November 1914, the Minister of Education, Dr. R.A. Pyne, devised a systematic approach by integrating pro-war material as an official part of the curriculum. For example, schools received a monthly pamphlet titled “The Children’s Story of the War.” The University of Toronto’s President, Robert Falconer, made appeals to students directly. On October 21, 1914, Falconer cancelled all lectures and held an assembly to encourage young men to enlist. Within a day, 550 students heeded the call. Young women in federated colleges also contributed to pressuring young men to enlist and even made it a competition to see who could sign up the most. These and other initiatives highlight how patriotic fervour was alive and well in the educational system. As pressure mounted, many young men abandoned their studies to join the military.

The age limit for enlistment in 1914 was 18 (later changed to 19). There were ways, however, of circumventing this restriction. Underage applicants could still enlist with a letter of consent from a parent. Others lied in the hope that their birth certificate would not be requested. When enlistment rates began to slow in 1915, recruiters were less inclined to make this request. The military also discontinued the right of parents to retract their underage sons from service.

The Department of Education facilitated the enlistment of students by offering accommodations and incentives. In 1916, the Department announced that it would reimburse secondary students for classes needed to complete their certificates after overseas military service. Or, if they were close to completion, they could obtain their certificates early. In 1916 and 1917, 395 and 154 secondary students respectively took this offer. Universities and colleges adopted a similar approach and granted a full year’s credit to enlisted students.

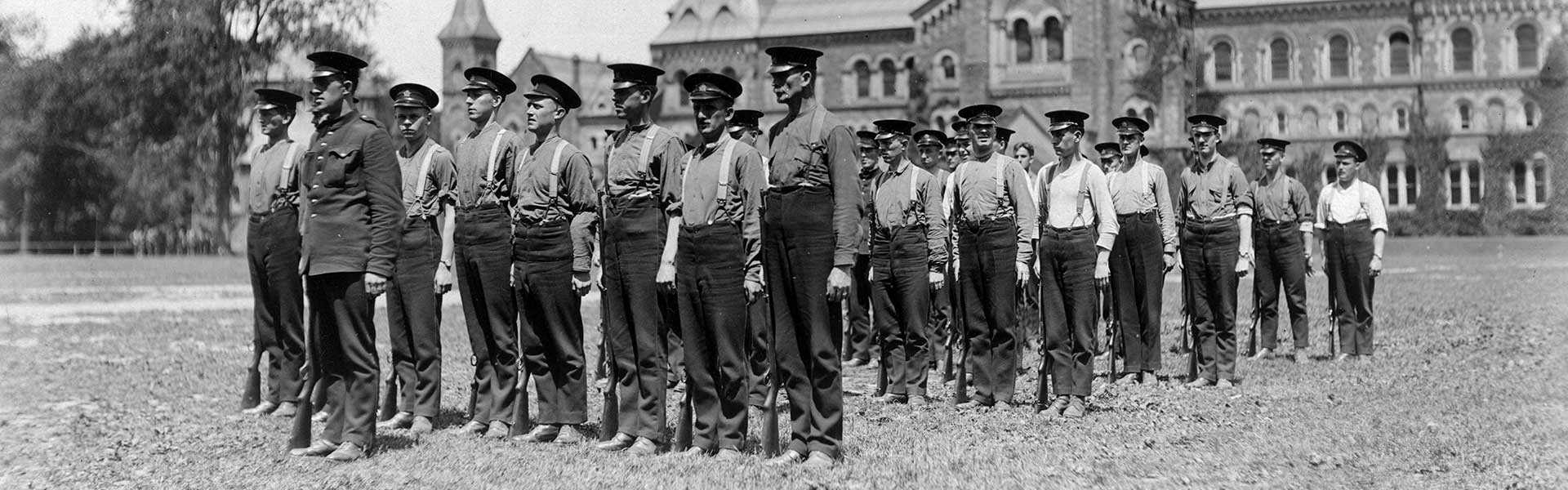

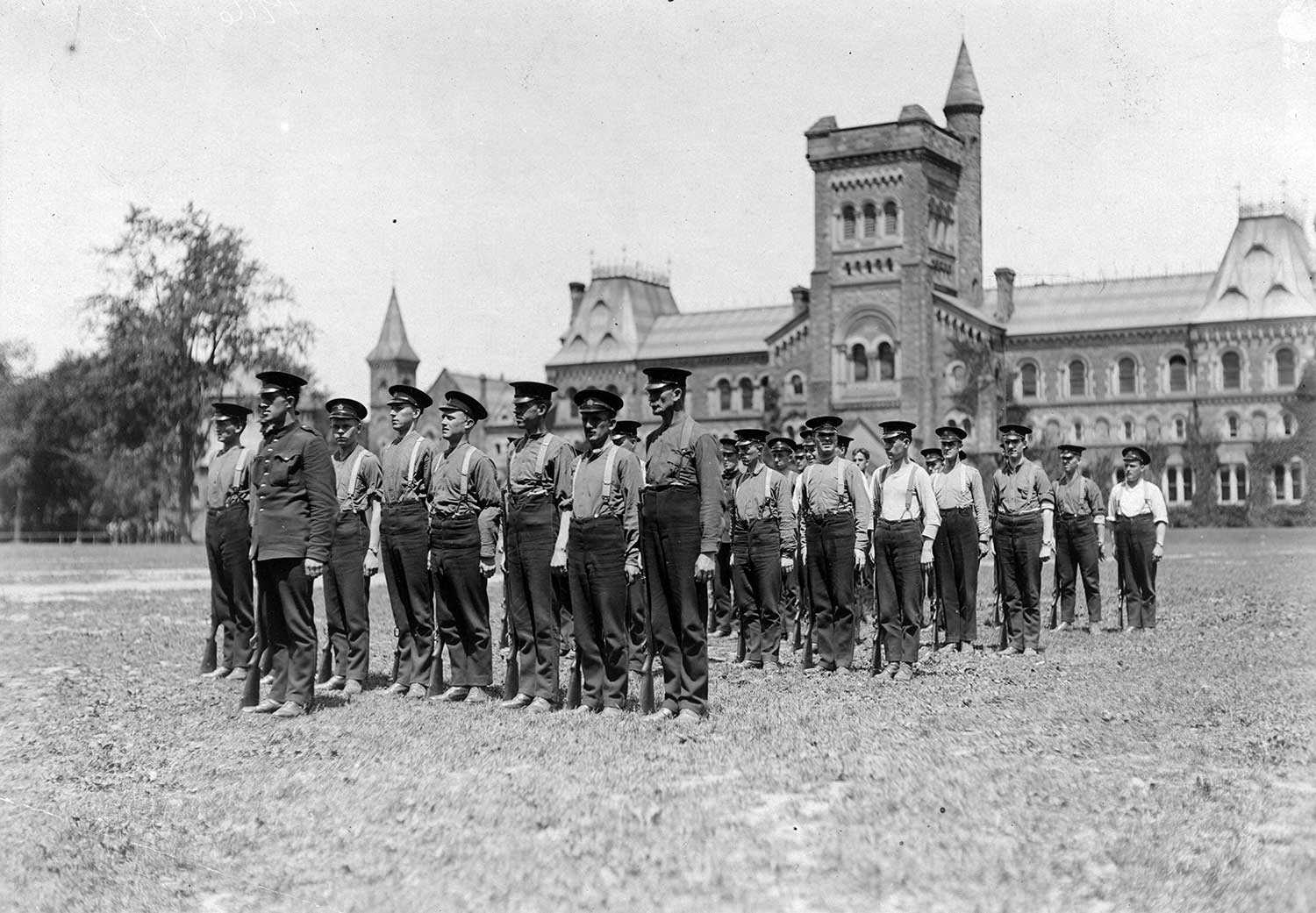

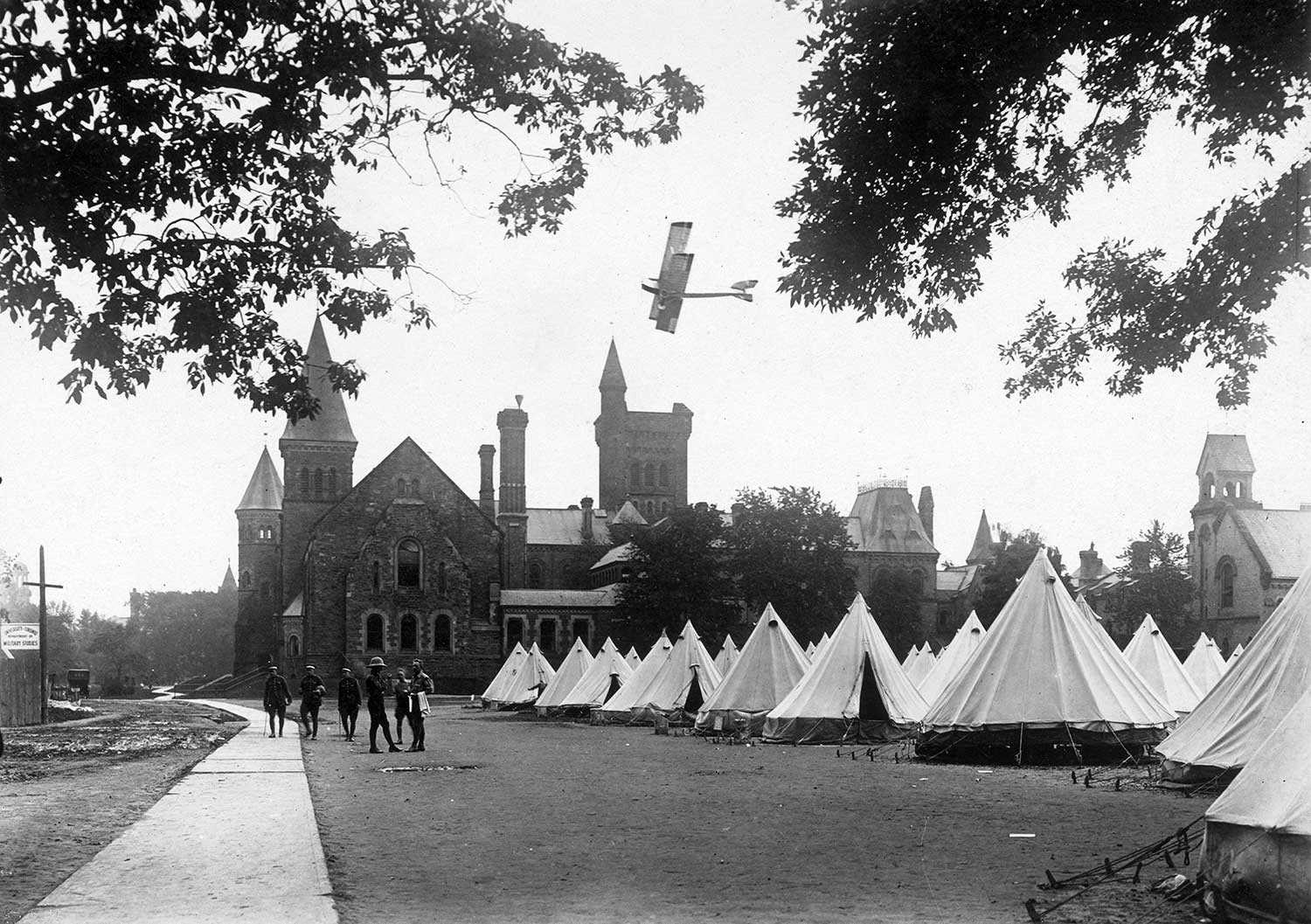

Colleges and universities had a direct role in mustering troops. Canadian Officer Training Corps, hospital units and artillery batteries were organized in association with universities across the province, including the University of Toronto, the University of Ottawa, McMaster, Queen’s, Western and the Ontario Veterinary College. New students entering university would undergo physical examinations to determine whether they were fit to fight and participate in military training. Students refusing the exam were prohibited from attending lectures and extracurricular activities.

By the end of the war, the military registered a total of 15,087 students. From Ontario, 1,025 undergraduate and 2,374 graduate students became officers, while 945 undergraduate and 453 graduate students joined the ranks. Throughout Canada, 60 per cent of all undergraduates were on active service. Those who remained on university campuses tended to be those who were not physically fit to serve, studied medicine or were barred for reasons of gender or race. Students from high schools also enlisted. According to historical estimates, the CEF had as many as 20,000 underage soldiers serving overseas.

Further mobilization

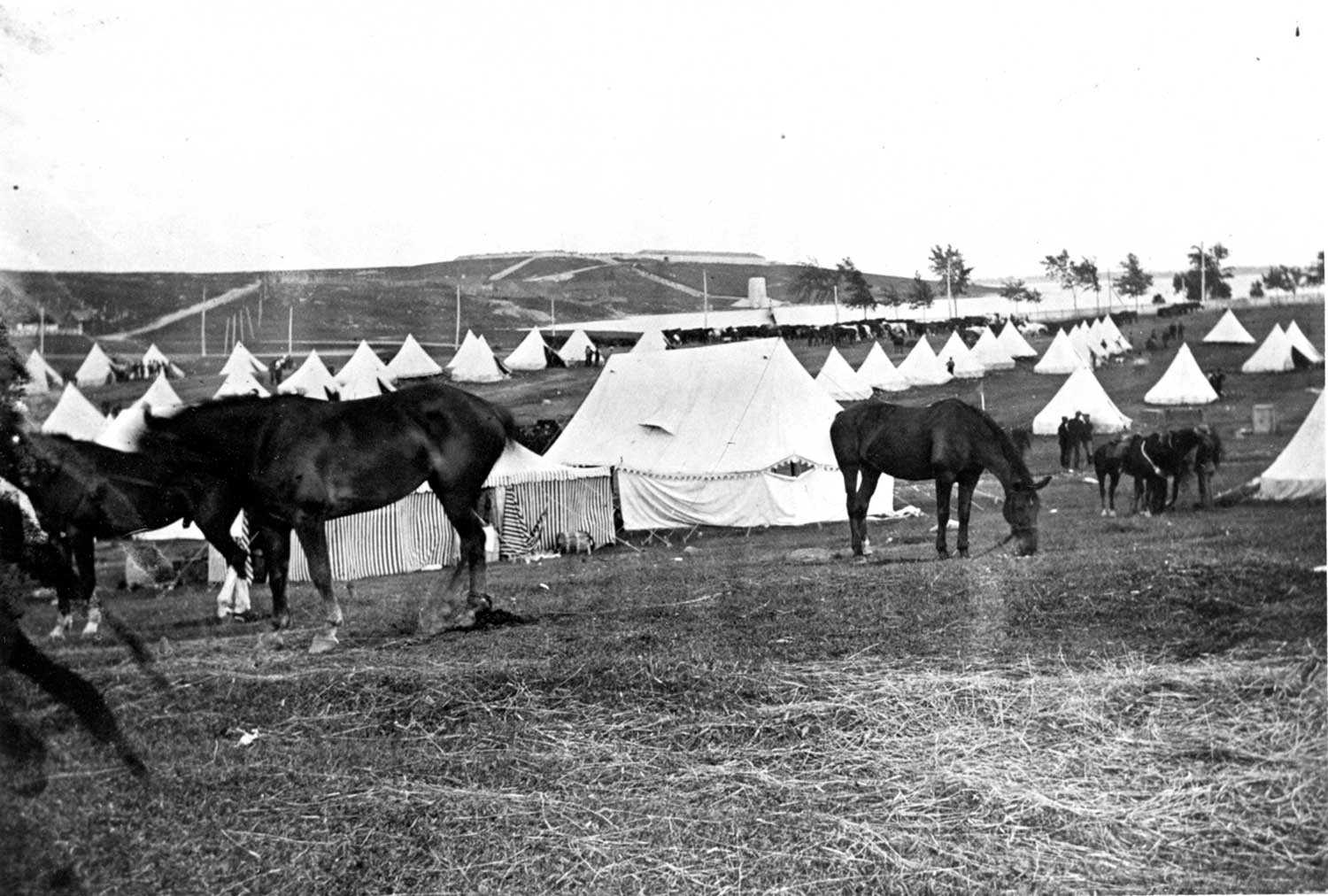

Universities made substantial contributions to the war effort. One area of contribution was through health and medicine. University labs were mobilized to supply medicines, antitoxins and medical supplies throughout the war. For instance, when the Exhibition Camp in Toronto suffered an outbreak of cerebrospinal meningitis in 1915, the Pathology Department of the University of Toronto produced the necessary medicine.

As another way to help address the sick and injured, some university campuses were converted into hospitals, including Queen’s University and the University of Toronto. The latter even organized a mobile hospital with 1,040 beds. The hospital travelled overseas and made dangerous voyages to England, Greece and the Western Front. School facilities were also converted into rehabilitation centres, such as Victoria College, and offered classes to re-educate soldiers.

Another contribution of Ontario’s universities and colleges was the improvement of military equipment and materials. For example, university metallurgists attempted to manufacture new alloys, while scientists improved flares, tested non-inflammable gases for submarines, and discovered new sources of helium for airships. School scientists were even employed to train pilots. In December 1916, the Air Board in London, England decided that Canada would establish an Air Force and undertake the supply of its equipment. The first flying units were stationed at the Long Branch Aerodrome in Mississauga, but as the program expanded, the University of Toronto donated part of its Convocation Hall and engineering buildings to become a training centre.

Educators more broadly contributed to the war effort in diverse ways. Some teachers led their students in patriotic activities, including producing clothing and bandages. Others led students in charity drives, such as collecting money for the Canadian Patriotic Fund. Educators also encouraged their students to participate in the Soldiers of the Soil campaign. By spring 1916, farmers struggled with a shortage of labourers. Since food production was paramount to an Allied victory, the problem warranted serious attention. In response, teachers in primary schools aided their students to garden in their backyards, community plots (such as those on school grounds) and vacant lots. To incentivize participation, older boys who volunteered as farm hands for at least three months could pass their grade without a final exam. Even boys in reform schools who volunteered were discharged as compensation for their services.

In 1917 and 1918, the shortage of agricultural labour was becoming critical, so policymakers recruited female students to their Soldiers of the Soil initiative. Known as farmerettes, these young women made their way to pick fruit and vegetables on the Niagara peninsula and elsewhere. It would not have been unusual if they were also given duties handling horses, pitching hay, driving trucks, planting, cultivating, weeding and more. In 1918, upwards of 18,000 to 19,000 high school students participated, representing 70 per cent of the province’s total enrollment. In addition, 2,400 female teachers, university students and married women answered the call to become farmerettes. Similar to women’s employment in war factories, women who became Soldiers of the Soil undermined prevailing gender norms that female labour would be ineffective for hard physical work.