Menu

The impact of the War of 1812 on Upper Canada

Introduction

On June 1, 1812, American President James Madison requested authorization from the United States Congress to declare war on the United Kingdom. Accompanying his request, Madison issued a war message outlining why he and his political supporters, known as the War Hawks, believed that war was necessary. Among the leading issues was the impressment of thousands of American seamen by the British Royal Navy. This action was deemed unjust and disruptive to American trade, and led to violent confrontations such as the Chesapeake-Leopard affair in 1807. In further violation of American maritime trading rights, the British prohibited American vessels from trading with France as part of an embargo to thwart Napoleon Bonaparte’s tightening grip on Europe. Adding to the American’s outrage was that the British maintained trade with French merchants under special licences. This seeming double standard revealed how the embargo maintained British commercial interests at America’s expense. Another allegation was that the British were conspiring to arm the Indigenous Western Nations’ communities, located in the Old Northwest, so that they could use armed conflict to halt American expansion. The War Hawks referred to the Battle of Tippecanoe on November 7, 1811 to support this allegation. Based on these and other reasons, the Senate ratified the declaration of war by a vote of 19 to 13. The House of Representatives also supported the war by a vote of 70 to 49. With the support of Congress, President Madison declared war on the United Kingdom on June 18, 1812. The British responded by denouncing the conflict’s legitimacy, stating that the Americans had sided with the tyrannical Napoleon to undermine freedom and liberty.

While Upper Canada had not provoked war, it became the Americans’ primary target. The province had a low number of professional soldiers for its defence. In 1812, there were only 5,600 British regulars between both Upper and Lower Canada. Of course, the British empire had tens of thousands of professional soldiers at their disposal, but substantial reinforcements for the army were unlikely while Napoleon reigned in Europe. Another reason why the fighting would be concentrated in Upper Canada was because New England remained largely neutral. As the votes in Congress highlight, America’s enthusiasm for the war was not unanimous. Indeed, New England sold supplies to the British military during the war. With a neutral border in the northeast, as well as a strong British naval blockade on the Atlantic coast, Upper Canada and the Great Lakes would become a primary outlet for American aggression.

The American commanders were confident that they could achieve a swift victory in Upper Canada. After all, the majority of Upper Canada’s population (between 60,000 and 80,000 at the time) were of American origin. With so many American settlers, some American commanders believed that Upper Canadians would welcome their army rather than resist it.

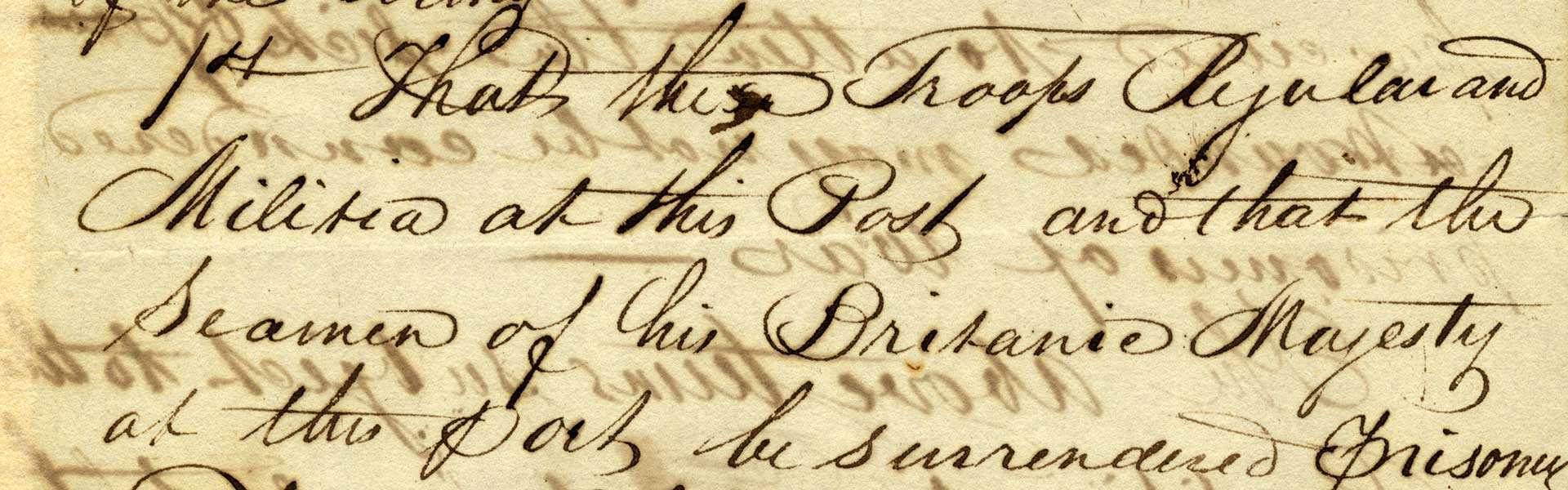

For the most part, these optimistic projections by the American forces proved false. After the British captured important American strongholds in 1812, the Upper Canadian militia became more willing to bear arms. The victories also inspired warriors from Six Nations, Seven Nations and Western Nations to join the British against the American forces. For many Indigenous warriors, the war was an opportunity to counter relentless American expansion, which had a reputation for brutality towards Indigenous peoples. By fighting alongside the British, Indigenous warriors were safeguarding their territory and attempting to win the Crown’s support for long-term Indigenous interests – which included Indigenous sovereignty.

By the end of 1814, neither side had secured a significant advantage. This led the British and American negotiators to compromise their desired objectives and sign the Treaty of Ghent on December 24, 1814. The war officially ended when the United States Congress ratified the agreement on February 17, 1815. Among the treaty’s provisions were the settlement of maritime rights issues, territorial boundaries and disarmament. Overall, the treaty’s terms strengthened the foundation for long-lasting peace between British North America and the United States. For the Crown’s Indigenous allies, who were not allowed to send representatives to the peace talks, the Treaty of Ghent would not prioritize their interests. The British abandoned demands for an independent Iroquoian state south of the Great Lakes. At best, they convinced the United States to restore Indigenous territory and rights to the standards of the pre-war period. The absence of any meaningful provisions for Indigenous interests meant that there were no counter-measures against the influx of hundreds of thousands of European immigrants who arrived after the war. As Indigenous communities became a shrinking minority, they were increasingly vulnerable to subjugation, assimilation and territorial encroachment. For Upper Canada’s white and Black residents – whose homes and possessions were plundered or destroyed - compensation claims took decades to be fulfilled. The onset of a post-war depression and poor harvests further intensified their struggle to recover from a war that they would not soon forget.