Menu

Battles in Upper Canada and the Great Lakes

Introduction

When the United States declared war on the United Kingdom, Upper Canada was ill-equipped to fight a large-scale war. William Hull, the American general leading the first invasion into Upper Canada, was so confident in victory that he expected little opposition. Initially, Hull’s optimism seemed well founded, but the British regulars, Canadian militia and Indigenous warriors won several battles in the summer of 1812. Their victories proved to the Americans that if they wanted to conquer Upper Canada, it would require a long and bitter struggle. The sections below explore the key battles in Upper Canada and the surrounding Great Lakes.

1812

The most promising strategy for the Americans to conquer Upper Canada was to circumvent it entirely. By capturing Montreal or Kingston, the Americans could disrupt Upper Canada’s supply lines and pressure the British army to surrender as they ran out of food and ammunition. While this was the ideal strategy, the American commanders did not adopt it in 1812. The American military was still in the early phases of its mobilization and did not have control of Lakes Ontario and Erie. Instead, the Americans launched a two-pronged offensive: one from Detroit into the southwest of Upper Canada, and the other in the Niagara Peninsula. This strategy was based on the belief that the British forces were too weak to withstand a direct assault.

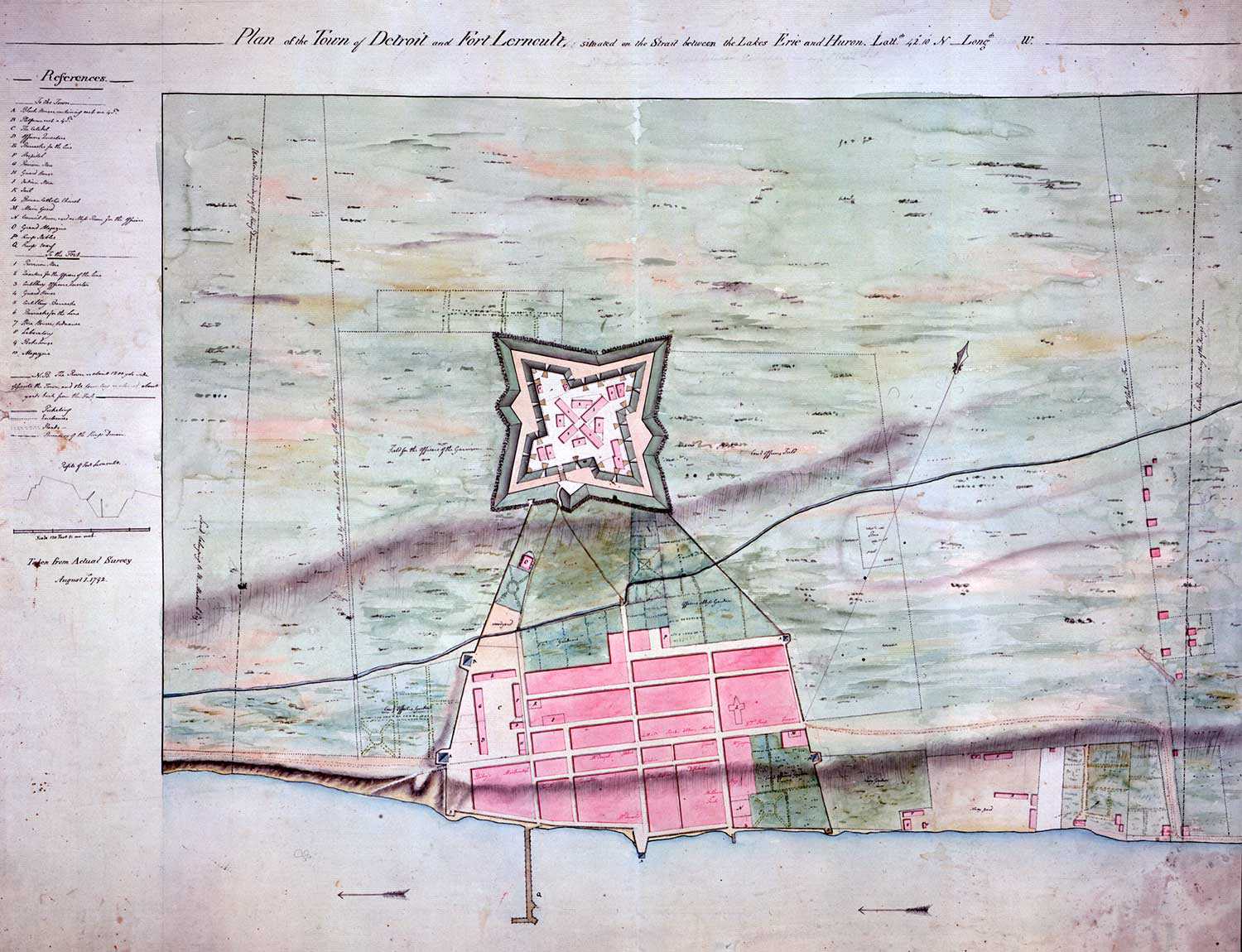

Surprisingly, the first major victory went to the British. The success was mainly attributable to the initiative of a low-ranking officer, Captain Charles Roberts, stationed on the northwestern shore of Lake Huron. When Roberts got word that the United States had declared war, he assembled a strike force to attack the American stronghold between Lakes Michigan and Huron. On July 17, Roberts led 45 British regulars, 180 fur traders and 400 Indigenous warriors to the nearby Fort Michilimackinac. Unaware that the war had begun, the American garrison failed to notice Roberts positioning a cannon that overlooked the fort. Surprised and outmanoeuvred, the American garrison surrendered without a fight. The capture of Fort Michilimackinac was significant because it inspired 600 warriors from the Western Nations, led by Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa, as well as warriors from Ojibwe and Ottawa, to join the British war effort. The victory was also beneficial because it unnerved General Hull, who had commenced the invasion of Upper Canada from Detroit a week earlier with 2,000 troops. On learning that Brock secured the support of Western Nations warriors, and having brought insufficient equipment to besiege Fort Amherstburg, Hull retreated to Detroit and awaited reinforcements.

Hull’s messengers travelling back to Detroit fell into an ambush set by Tecumseh. The American general’s letters were taken and delivered to Brock, allowing him to learn that Hull feared an attack against Detroit. Knowing that the American army was hindered by weak leadership, Brock and Tecumseh besieged the American army at Fort Detroit. They used clever tactics to intimidate the American garrison, including exaggerating the number of their Indigenous warriors by repeatedly moving the same troops through the woods within view of the garrison. Meanwhile, General Hull was sick, drank heavily and neglected his duties. The former veteran of the American Revolutionary War lost the will to fight and surrendered. It was an astounding victory for the British because 2,200 American soldiers (including 600 regulars) were taken prisoner. The British also seized 35 cannon, 2,500 muskets, 500 rifles, ammunition and a brig.

General Hull may have failed in his duties, but that did not stop General Van Rensselaer from commencing his invasion into the British side of the Niagara Peninsula. Under Van Rensselaer’s command were approximately 6,000 soldiers (half were regulars). He had an additional 100 Seneca warriors from New York and another 2,000 militia en route. On the British side, there were less than 1,000 regulars, 600 militia and a reserve of roughly 600 militia and Indigenous warriors. Wanting to avoid losing strength due to desertions and disease, and further worried about changing weather conditions, Rensselaer commenced his invasion and crossed the Niagara River on October 13.

The initial foray went poorly. The river’s current swept transport ships downstream, and the American soldiers who landed came under heavy fire from the British artillery on Queenston Heights. Eventually, a party of American soldiers attacked the British battery and overtook the position. General Brock, who arrived from Fort George, led a counterattack up the hill and charged alongside 200 soldiers. Brock, shouting fiery words of encouragement, was shot in the chest and killed. Lt.-Col. John Macdonell continued the assault, but he was also wounded. Although the Americans held the advantage, John Norton and the Six Nations warriors from Grand River held off the American’s from advancing. This allowed Major-General Roger Sheaffe to bring British and Indigenous reinforcements from Fort George and overtake the American position. At the end of the Battle of Queenston Heights, 500 Americans were killed or wounded and 900 were captured. In comparison, the British and their Indigenous allies only suffered 19 killed, 77 wounded and 21 missing. It was a decisive defeat for the Americans, compelling Rensselaer to step down from command shortly thereafter. Brigadier-General Smyth was appointed as his replacement, but his attempts to cross the Niagara River also failed.

On the Great Lakes, the War of 1812 took shape more gradually. On Lake Ontario, the British began the war with an advantage on both lakes. Brock sought to capitalize by attacking Sackets Harbor, New York and prevent the Americans from creating a fleet. Prevost negotiated a ceasefire, however, hoping that a recent change in British policy regarding American trade would suffice in ending the war. But Prevost was mistaken, and the Americans used the ceasefire to consolidate their naval presence on the Great Lakes. By late fall 1812, the opportunity to strike Sackets Harbor had passed. Captain Isaac Chauncey arrived to oversee American operations on Lakes Ontario and Erie, and American sailors and supplies flooded into Sackets Harbor. On November 8, the Americans launched a fleet into Lake Ontario composed of seven warships, pressuring the British fleet to withdraw to Kingston. The Americans also added the Madison on November 26. The 24-gun ship made it the most formidable warship on Lake Ontario, further securing American naval control. On Lake Erie, the Americans began constructing a naval base at Presque Isle. The port’s geographical features prevented the British from making a direct attack, but it would also make launching new ships difficult. Overall, the British grasp on Lakes Ontario and Erie was weakening by the end of 1812 because the Americans could direct more resources towards the construction of naval bases and fleets.

1813

The American invasion of Upper Canada in 1812 was a resounding defeat, but the American will to fight remained strong in the new year. As long as the bulk of the British army was preoccupied with Napoleon, the Americans maintained the prospect of overwhelming Upper Canada’s defenders.

In January, American Brigadier-General William Harrison led an army of over 6,000 soldiers to recapture Detroit. After securing the nearby settlement of Frenchtown, Major-General Henry Procter and Tecumseh led a surprise counterattack with their force of 500 soldiers and 600 warriors. The gamble proved worthwhile because the Americans suffered 400 casualties. An additional 500 soldiers were also taken prisoner. Following the defeat, the American army retreated further southwest and constructed Fort Meigs to fortify their position.

The following month, the British launched another attack. This time, the objective was Ogdensburg, New York – located on the American side of the St. Lawrence River. Opposing Ogdensburg was the British stockade around the house of Col. Edward Jessup and Fort Wellington. Despite the nearby British garrisons, the Americans at Ogdensburg remained a constant threat to the British supply lines. Seeking to end this threat, Lt.-Col. George Macdonell sortied from Fort Wellington against the instructions of Procter and succeeded in capturing Ogdensburg. The British forces set fire to the American fort and seized their supplies. Importantly, Macdonell’s bold action secured the supply route for the remainder of the war. With these victories in January and February, the British and their Indigenous allies made a successful start to the year. The tides of war, however, would soon shift against them.

The naval dominance of the American fleet on Lake Ontario meant that the Americans could target fortifications and settlements along the coast with greater ease. It also provided a direct route to Kingston and Montreal. General Dearborn and Commodore Chauncey believed, however, that both positions were too well defended at the beginning of the year and instead chose to attack Upper Canada’s capital, the town of York.

Strategically, York was not very important, but its weak defences made it an easy target to capture ships and military supplies. In late April, the Americans sailed across Lake Ontario with an armada of 12 schooners, one brig (Oneida) and one corvette (Madison). In total, there were 900 sailors, over 60 cannon and an army of 1,700 soldiers. To put the size of this force into perspective, the invasion force was larger than York’s population of 625 residents and the British garrison of 300 regulars and roughly 500 militia, dockyard workers and Indigenous warriors. With the odds stacked in their favour, the Americans commenced the Battle of York on April 27.

The American attack quickly overran the British defences. Conceding the loss of Upper Canada’s capital, Major-General Sheaffe shifted his attention to denying the Americans their spoils before retreating to Kingston. He ordered his troops to blow up York’s grand magazine – the main storehouse of explosives and ammunition. The massive explosion caught the Americans by surprise. Stone debris fell in the surrounding area, killing or wounding 250 American soldiers. Among the fatalities was the American General leading the assault, Zebulon Pike. The British also managed to destroy some of their ships and supplies.

During the occupation, some houses and stores were looted without military sanction. York’s public buildings, including the parliament buildings, were set on fire. Although the Americans succeeded in pillaging York, it came at a higher cost than anticipated. The Americans suffered 320 casualties, while the British suffered 157, including 13 Indigenous warriors. Having plundered York, the Americans had no reason to continue their occupation. On May 8, the American army boarded Commodore Chauncey’s fleet and sailed for the Niagara Peninsula.

Shortly after Chauncey’s fleet arrived at Niagara, it commenced bombarding Fort George. The naval attack supported the deployment of 4,000 to 5,000 American soldiers. With only 1,000 British soldiers and Indigenous warriors, the American attack was once again overwhelming. Within days, British Brigadier-General John Vincent ordered a large-scale retreat from the Niagara frontier and regrouped at Burlington Heights. Commodore Yeo, commanding the British navy on Lake Ontario, attempted to exploit the preoccupation of Chauncey’s fleet with a surprise attack against Sackets Harbor. Unfavourable winds, however, prevented it from inflicting meaningful damage. Back on the Niagara Peninsula, General Dearborn advanced with 3,000 soldiers towards the British position camped at Stoney Creek on June 5. The British gathered intelligence on the American position and, despite being heavily outnumbered, Lt.-Col. John Harvey led a surprise attack at night. The battle was chaotic. Although the British suffered heavy casualties, they captured numerous American officers. Shortly after, the British fleet arrived and General Dearborn ordered the American army to retreat to Fort George.

Later in June, another significant battle would occur in the Niagara Peninsula – the Battle of Beaver Dams. On June 24, 600 American soldiers were dispatched to harass the British posts along the Niagara River. Laura Secord, a resident of Queenston, overheard the Americans discussing the attack. Eager to warn the British commanders, she embarked on a treacherous journey through 30 km (19 miles) of woods in the dead of night. Secord’s warning confirmed the suspicions of an impending assault. This led John Norton to organize an ambush so that they could intercept the Americans at Beaver Dams. Accompanying him were 180 warriors from Seven Nations, 200 warriors from Grand River, 12 warriors from Thames River, 70 warriors from Ojibwe and Mississauga, and a small group of militia. To their delight, the Americans halted their column in the middle of the trap and an intense struggle ensued. After hours of fighting, the Americans were forced into an impossible position and surrendered. The Indigenous warriors suffered 50 casualties, including five chiefs, but the Americans had 100 casualties and the remaining 500 soldiers were taken prisoner.

The British and their Indigenous allies withstood the American offensive on the Niagara Peninsula and achieved impressive victories. On the Michigan frontier, however, the Americans regained the advantage. Procter and Tecumseh attempted to push the Americans out of Fort Meigs in April and May, as well as Fort Stephenson in August, but the offensives failed. Meanwhile, on Lake Erie, the Americans launched new ships and defeated the small and neglected British fleet led by Captain Robert Barclay. Having lost control of Lake Erie and failing to dislodge the American army, Procter ordered the retreat from Michigan territory. Tecumseh reluctantly agreed. As Procter and Tecumseh led their force of 950 soldiers, militia and warriors back into Upper Canada, they were intercepted by the Americans in Thames Valley. In this battle, known as the Battle of Moraviantown, the American forces held the numerical advantage by three to one. General Procter and some soldiers and warriors escaped, but Tecumseh was killed in action. His death had such a profound impact on the morale of the Western Nations warriors that they signed a ceasefire with the American General. Tenskwatawa would be one of the few Western Nations warriors that continued fighting with the British.

Before the end of the fall of 1813, the Americans finally launched a major offensive intent on capturing Montreal. Leading the American offensive was General Dearborn’s replacement, Major-General Wilkinson. The offensive began when the American fleet departed from Sackets Harbor with 7,000 to 8,000 soldiers, most of whom were from the Niagara frontier. Commodore Chauncey sailed his troop laden ships directly across Lake Ontario to the mouth of the St. Lawrence River. He was confident in the superiority of his fleet because he had recently chased the British fleet to the safety of Burlington Heights. This confrontation is known as the Burlington Races and resulted in few casualties.

The attack through the St. Lawrence River did not go as planned. Reinforcements from New York were not deployed, American transports came under unexpected fire from the Canadian militia, and Wilkinson became very ill. On November 11, a major battle occurred called the Battle of Crysler’s Farm. American Brigadier-General John Boyd commanded 4,000 disembarked troops and came under attack by Lt.-Col. Joseph Morrison, who led a force of 800 British regulars, militia and Indigenous warriors. The battle was fought on open ground, which was ideal for the well-trained British regulars. In the end, there were over 300 American casualties and 100 American soldiers taken prisoner. The British force suffered half as many casualties. The Battle of Crysler’s Farm was a blow against the American campaign. Combined with the absence of the expected reinforcements, a shortage of supplies and the approaching winter, the American commanders abandoned their offensive.

The redeployment of American troops to participate in the attack against Montreal left the American Niagara frontier lightly guarded. To capitalize on this weakness, Lieutenant-Governor Drummond and Major-General Riall went on the offensive in December, leading the American Brigadier-General George McClure to abandon Fort George. Before retreating across the Niagara River to garrison Fort Niagara, McClure ordered his soldiers to burn the nearby village of Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake). It was a crime that would not soon be forgotten. The British and their Indigenous allies continued their advance. After surprising the American garrison at Fort Niagara, they seized it with little bloodshed and captured 350 American soldiers. As the offensive continued, American ships and towns were captured. In retribution for Newark, Riall burned some of the nearby towns and villages, including Lewiston, Black Rock and Buffalo. It was a dark end to a bloody year of fighting.

1814

By the beginning of 1814, neither the British nor the Americans had gained a significant advantage in the struggle for Upper Canada. The Americans took control of Lake Erie, but the British and their Indigenous allies captured Fort Niagara and Fort Michilimackinac. Meanwhile, control of Lake Ontario continually shifted between the Americans and British as they both launched new and larger warships. Despite heavy losses with little gain, intense fighting would continue in 1814. The American army was better trained and equipped than in preceding years. This advantage, however, would not last long. Following Napoleon’s abdication in April, the British deployed 14 battle-hardened regiments and experienced generals for the war effort against the United States.

The first half of 1814 consisted mainly of smaller expeditions and skirmishes along Upper Canada’s frontiers. Among the most notable was Campbell’s Raid. An American army of 800 regulars and militia led by Lt.-Col. John Campbell attacked the settlements of Dover and Ryerse’s Mills, burning them to the ground and pillaging nearby communities. The destructive raid was the American’s response to the burning of Buffalo and other settlements at the end of 1813. The main reason for these more limited engagements was because the British launched new ships in the spring and regained control of Lake Ontario. This meant that the Americans could not attack Kingston or Montreal from the St. Lawrence River until they regained naval supremacy. There was an attempt by General Wilkinson to assault Montreal from New York in March, but he was unwilling to commit to a large-scale attack after his forces were easily repelled.

Seeking to gain some leverage for the peace talks during the latter half of the year, the American commanders focused on the Niagara Peninsula and Fort Michilimackinac. The Niagara offensive began in July and Major-General Jacob Brown was appointed to oversee the campaign. Brown commanded a numerically superior force in comparison to the British, but he also had to contend with the new British forts, Fort Mississauga and Fort Drummond, which were constructed on the northwest side of the Niagara River and Queenston Heights respectively.

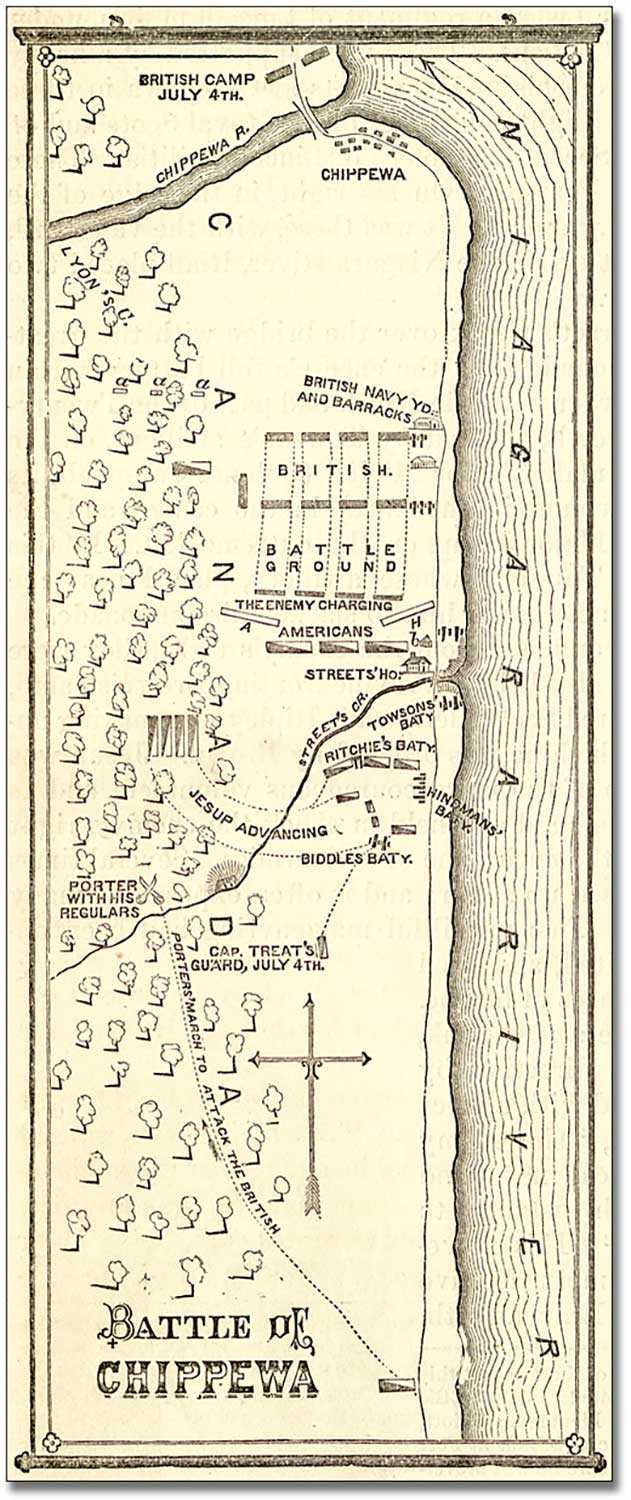

At the outset of the campaign, the American force easily surrounded Fort Erie and forced the British garrison to surrender. General Riall attempted a counterattack at Chippawa, but he underestimated the opposing force and suffered a costly defeat. The Battle of Chippawa would be a significant battle because it led to the withdrawal of most Six Nations warriors. During the fight, warriors from Six Nations Grand River and New York clashed, resulting in over 100 casualties. The warnings of peace chiefs at the beginning of the war – that the participation of Six Nations would lead to fratricide – echoed loudly after Chippawa. The staggering losses weighed heavily on the remaining warriors, and most agreed to withdraw from the war or limit their involvement.

Following the Battle of Chippawa, the Americans held the initiative and pressed their attack. General Brown advanced to Queenston, but Chauncey’s fleet failed to arrive in support. Consequently, Brown felt that his position risked being cut off from supply, so he retreated. The withdrawal prompted Riall to chase Brown, leading their armies to get locked into battle at Lundy’s Lane. A fierce struggle ensued over the British artillery’s hilltop position. Eventually, Brown ordered a retreat. In the aftermath, losses were nearly equal. The Americans suffered 900 casualties and the British 800. Such high casualty rates on both sides made it the bloodiest battle of the war.

In August, momentum had shifted to the British and they went on the attack in the Niagara Peninsula. Drummond ordered his troops to besiege Fort Erie, but having done insufficient damage to the defences, the assault resulted in 366 casualties and 539 missing soldiers. The Americans, who retained control of the fort, only suffered 84 casualties. It was a crushing defeat for the British and their remaining Indigenous allies. When Major-General Izard reinforced the American position with 4,000 troops in November, he decided to destroy the fort and then march to the American side of the Niagara River. The last battle between the two armies on the peninsula was unclimactic. Izard led a small force to Cook’s Mills, which drove away the British force and allowed Izard to destroy the supply of grain and flour.

With the Americans’ unsuccessful attempt to recapture Fort Michilimackinac in August, the United States ended 1814 with no substantial gains. Even beyond Upper Canada, there were some important battles, but little ground was gained by either side. For instance, the British attacked Washington, D.C. in August and faced minimal resistance as they approached through Bladensburg, Maryland. As retribution for the destruction at York, the British burned Washington’s public buildings, including the President’s House (now known as the White House). The British also made an unsuccessful offensive in New York. Prevost led an army that crossed into New York along Lake Champlain. Before a major battle was fought, Prevost ordered a retreat because the supporting navy on the lake was defeated.

Overall, the battles of 1814 failed to give the British or American negotiators greater leverage during their peace talks in Belgium. The British held a slight advantage from occupying Fort Michilimackinac and Fort Niagara, but war weariness sapped their will to continue the fight. On December 24, 1814, the negotiators reached an agreement, which the United States Congress later ratified on February 17, 1815.