Menu

Life in a war zone

Introduction

Before the War of 1812, the lives of most of Upper Canada’s inhabitants involved hard work and offered few comforts. Even for the most skilled homesteaders, subsistence was precarious; bad harvests could bring a family to the brink of starvation. Unfortunately for these residents, life would become even more difficult with the onset of the War of 1812.

Those residing inland and northeast of Kingston continued to live in relative safety, but they still had to cope with rising costs of living and shortages of food and labour. Meanwhile, the inhabitants near the American border and the shores of Lake Ontario lived in constant danger of their homes being looted and destroyed. When the war ended, exceptional hardships continued as rewards for wartime service, or compensation for wartime losses, were entangled in administrative delays and complications.

For the Crown’s Indigenous allies, life did not improve in any meaningful way. The respectability of Indigenous wartime service faded over time, and colonial administrators in later decades adopted policies to encourage assimilation and marginalization. The history of the War of 1812, particularly for those who lived during the late 19th century, became the basis for inspiring stories of heroism and a nascent Canadian nationalism. Yet, for many of those who lived through the war, it was not so easily romanticized.

Wartime prosperity and hardships

Few residents of Upper Canada rejoiced at the news that the United States had declared war on the United Kingdom. Conversely, a few Upper Canadians welcomed the war for its economic opportunities, particularly among the economic elite. The British military’s demand for supplies was insatiable, thereby providing lucrative opportunities for well-capitalized and well-supplied merchants. The best of them had even gotten wind of the war before it officially began and stockpiled goods in anticipation. Another group of people that profited from the war were innkeepers and tavern owners. With increased traffic from refugees, merchants, couriers and army officers from both sides of the conflict, these establishments could do exceedingly well. Among them was Widow Willson’s tavern near Niagara Falls. It was managed by Debora Willson and her two daughters after the death of her husband. The tavern was visited by both American and British officers, depending on who controlled the area. The tavern’s location near the frontlines, however, put Willson in a precarious situation. On at least one occasion, Debora Willson was compelled to divulge the British position to an American general, who then proceeded to fight the Battle of Lundy’s Lane. After sustaining heavy casualties, the Americans transformed Widow Willson’s tavern into an emergency dressing station.

Like the services provided by inns, those who operated boarding houses also benefitted from the wartime economy. For smaller establishments, profits were most likely used merely to offset rising wartime prices.

Besides these well-positioned merchants and business owners, the war tended to intensify economic hardships. With some goods rising as much as 300 per cent, cash-strapped residents struggled to afford food, equipment and the few available comforts. Wartime loans could be acquired, but they were expensive and led to usury. For instance, one merchant, Isaac Wilson, received a 10 per cent return for 20-day loans. Some residents may have been forced to accept these rates because working hard had no guarantees of an immediate cash return. With money in low supply, it was not uncommon for skilled workers and soldiers to be unpaid for extended periods. Even Upper Canadians on farmsteads struggled to obtain cash as the poor harvests of 1812 and 1814 left minimal surplus to sell.

As men enlisted and left their homes to serve in the military, women took on even greater responsibilities for managing households and farms during the war. Running the family business or farm, teaching, clothing trades, nursing and domestic services were among the most common occupations for women. For those women whose husbands would not return, these wartime roles could become lifelong commitments.

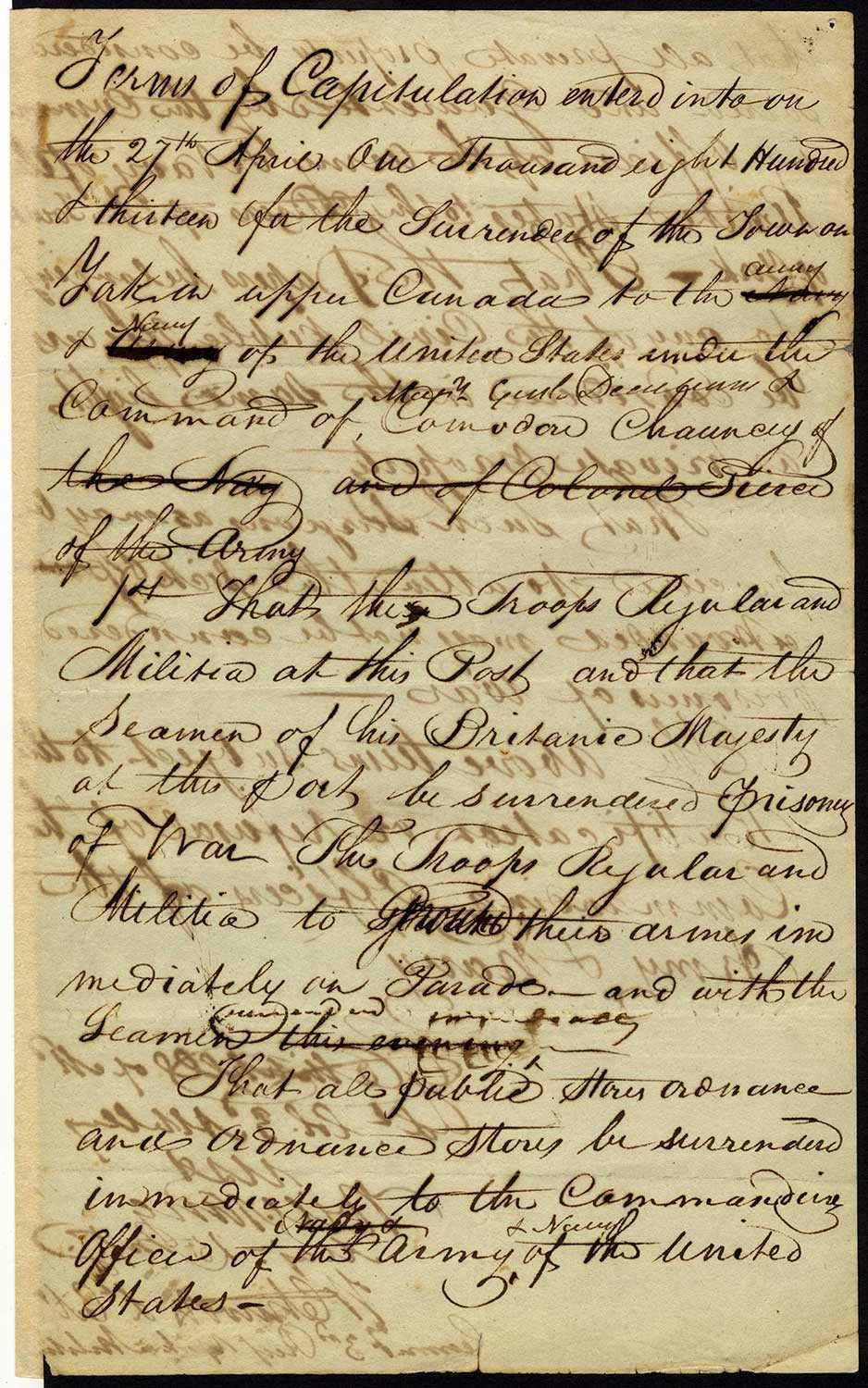

Rising prices and scarce supplies of cash caused many difficulties, but being robbed was much worse. When the Americans captured York in April 1813, American soldiers prowled the town, looting easy targets such as abandoned homes. General Dearborn oversaw the occupation, and while he did not sanction the looting, it was encouraged by his neglect and indifference. When the American soldiers returned in July for the Second Invasion of York, the looting was even more widespread.

In the southwestern region of Upper Canada, the looting and pillaging were relentless. Following Proctor and Tecumseh’s defeat in late 1813, the southwest region of Upper Canada became a frontier vulnerable to American raids. The American army sent out raiding parties and also relied on the help of treasonous Upper Canadians. Among the traitors was the wealthy landowner Ebenezer Allan and the former parliamentarian Joseph Willcocks, the latter having led the infamous group of marauders known as the “Canadian Volunteers.” These bandits wreaked havoc throughout the land, robbing homes at gunpoint, burning crops, destroying mills, capturing militia officers and gathering intelligence. These marauders were effective because they used their familiarity with the locals and the land.

Since the British military’s protection was unreliable, some residents formed vigilante groups and fought back. For instance, on November 11, 1813, Colonel Henry Bostwick led a group of civilians and former militia into battle against a raiding party. They emerged victorious after killing five raiders and capturing 16. Other residents were inspired by their success and took up arms to fend off raiders. A special court was convened at Ancaster to address the increasing cases of treason. The trials, known as The Bloody Assize, led to the execution of eight men. But despite these efforts, the greater part of the province west of the Grand River was deprived of its resources and residents were forced to cope with widespread food shortages.

The defeat of Procter and Tecumseh placed the people living on the Grand River Tract in immediate danger. With most of the Six Nations warriors fighting on the Niagara Peninsula, 1,400 men and women of the Grand River Tract fled their homes and established a refugee camp at Burlington Bay. It was a precarious position because, while it offered the security of the British military, it also meant they were closer to the frontlines.

The Six Nations people from the Grand River were joined by other refugees, including white and Black residents from the surrounding area. Survival at the refugee camp was a harrowing experience. Food shortages caused intense hunger for days on end. With the arrival of spring in 1814, most of the Grand River refugees were compelled by hunger to return home and plant crops. It was a great risk because the threat of raids remained. After the Battle of Chippawa, however, most Six Nations warriors returned home so that they could protect their communities. The precaution was warranted, especially because of the ruthless intensification of American and Upper Canadian raiders in 1814. Civilians were robbed of their clothes and furniture, livestock was slaughtered and entire villages such as St. Davids in the Niagara region were turned into smouldering ruins.

British soldiers, militia and Indigenous warriors also went to the homes of Upper Canadians in desperate search of supplies. Combatants were often left without pay for extended periods and struggled to eat. Pressured by slow starvation, soldiers and warriors were driven to steal supplies from local farms and mills. Military officers also took supplies from locals. When civilians in Kingston refused to surrender their food, Major-General Procter invoked martial law, forcing them to heed the military’s demands. Civilians could expect to receive compensation after the war. It meant, however, that civilians would have to deal with further wartime pressure to make ends meet.

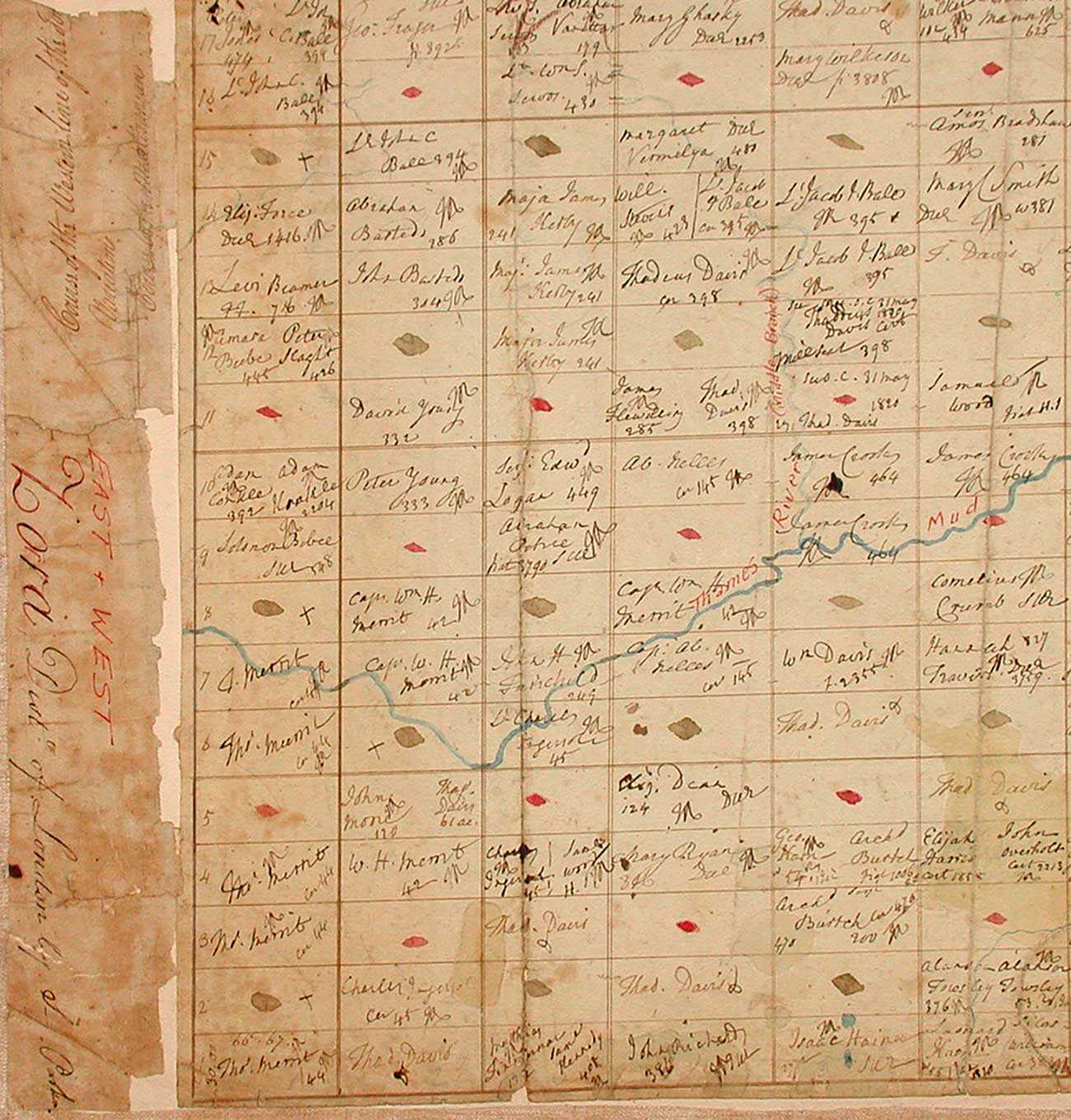

Returning to peace

For some civilians, the transition to peace began with their return home. Numerous refugees took shelter near the British military outpost at Burlington, but others found sanctuary near Kingston and York. The civilians who lost property because of the war could apply to the Board of Claims for compensation. There would be four different compensation boards between 1813 and 1823. Payments for damages to property were awarded to claimants from the fourth compensation board, which completed its work in 1826. The board recorded a total of 2,055 claims. About one-third of all claims were from residents in Niagara, and constituted almost half the value of all claims in the province. The other areas in Upper Canada with a high number of claims included Western, London and Gore districts. To the utmost frustration of the claimants, payment was painstakingly delayed. The government of Upper Canada was struggling to raise funds needed for the compensation and awaited the British Treasury to cover half the cost. It was only on March 4, 1837 – over two decades after the war ended – that the government of Upper Canada authorized payment for outstanding claims.

Another part of the transition to peace was the demobilization of the militia. Similar to compensation for losses, rewards for wartime service could be immensely frustrating. Initially, militia units raised by the British military authorities were ineligible for land grants and cash gratuities. The militia in flank companies and incorporated battalions, being raised under the province’s jurisdiction, were eligible, but still many received their land as late as the 1820s. Receiving pensions was even worse as parliament issued pensions for the militia as late as 1875.

Land grants were also racially discriminatory because Black soldiers received half the amount of land as their white counterparts. Black militia also had the disadvantage of being given land in distant areas, preventing them from offering each other mutual assistance, which was needed to develop the land and obtain full entitlement. The exception to this were the land grants given to Black veterans in Oro Township near Barrie. By 1831, nine Black veterans had settled in Oro, and while the community would reach 100 inhabitants. Sadly, the settlement failed because of its infertile soil.

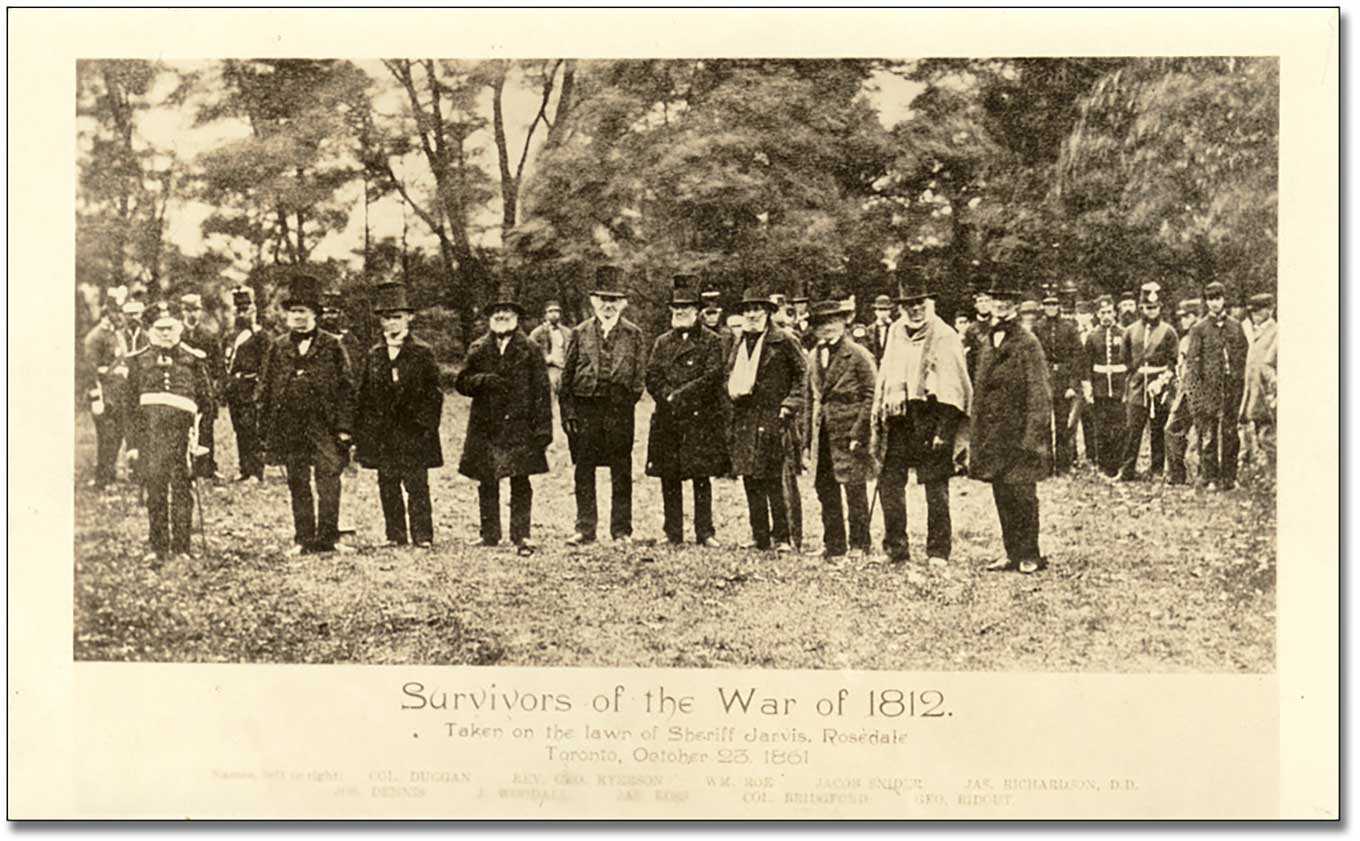

The recognition for wartime service among civilians was also delayed. In 1860, the then-Prince of Wales visited Niagara to participate in a ceremony unveiling a monument to honour Sir Isaac Brock. During his visit, the Prince received many petitions from civilians who sought recognition for their wartime contributions. Among them was Laura Secord. During the war, Secord travelled 30 km (19 miles) through the woods at night to warn the British of an impending attack. The Prince obliged the request, and after 50 years, Secord received recognition from the Crown and an award of £100 in gold. She died in 1868 at the age of 93.

For Indigenous warriors, the importance and sacrifice of their wartime service did not equal their rewards. During the peace talks, British negotiators abandoned the demand to create an independent Iroquoian state south of the Great Lakes. American opposition was stern, and the British did not believe that this demand was worth continuing the war. For the Six Nations of the Great Lakes, this meant that white settlers would continue to encroach on their ancestral lands. Similarly, Western Nations that allied with the British were enveloped by relentless American expansion. To ensure that the British could not support Western Nations’ resistance, the United States government passed regulations prohibiting the British from trading with Indigenous tribes on American territory. The Americans also constructed forts on the frontier to block trade routes.

For the Indigenous communities within Upper Canada, post-war shifts in British policy undermined Indigenous interests. By the early 1820s, the significance of the Six Nations as military and diplomatic allies was already declining. This change encouraged colonial administrators to undertake more concerted efforts to assimilate Indigenous people, acquire Indigenous land and undermine Indigenous independence. For example, proceeds from Six Nations land sales were forcibly invested into the Grand River Navigation Company. Six Nations had no representation on the company’s board of directors, despite holding 80 per cent of the company’s stock, nor did Six Nations receive company dividends. Meanwhile, Six Nations people struggled during freezing winters and poor harvests. To their dismay, the Grand River Navigation Company hindered the sustainability of the Grand River people because it destroyed fertile lands and potent fishery locations to make the Grand River navigable. Ultimately, this project failed and, in 1861, the company went bankrupt. Such blatant disregard for the autonomy and interests of Six Nations did not honour their legacy as the Crown’s allies, nor their wartime sacrifices.